What Are Wicked Problems and How Might We Solve Them?

- 1.2k shares

- 2 years ago

Complex socio-technical systems are intricate societal and global problems, challenges that designers strive to define human issues, understand their far-reaching implications, and address carefully. Designers try incremental steps toward sustainable solutions, as they are difficult to approach and understand.

“The designer simply cannot predict the problems people will have, the misinterpretations that will arise, and the errors that will get made.”

— Don Norman: Father of User Experience design, author of the legendary book The Design of Everyday Things, co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group, and former VP of the Advanced Technology Group at Apple.

See why complex socio-technical systems can be wickedly intricate but not hopelessly impossible.

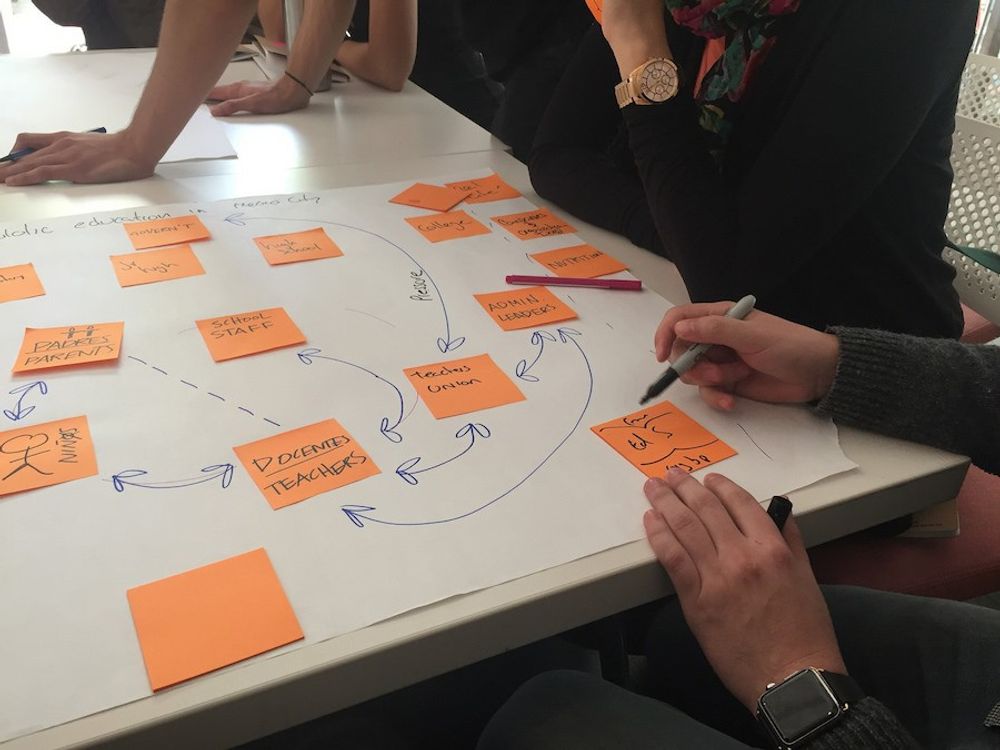

Cognitive science and user experience expert Don Norman differentiates complex socio-technical systems from wicked problems. Although the two are essentially the same, Norman states the latter term is overused and has too many different meanings. Nevertheless, wicked problems are:

Difficult to define.

Complex systems.

Difficult to know how to approach.

Difficult to know whether a solution has worked.

Many global problems have these qualities. They’re too massive and intricate to “solve” — take world peace as an example. But more solvable-looking problems (e.g., global warming) also have hordes of complex, intertwined issues within them. Often, these smaller issues are entangled with political agendas and various factors that make them hard to understand, let alone solve. What appears to be a simple approach is often an insignificant part of a very large problem. For example a socio-technical system could be (e.g.) healthcare-related, and some fantastically straightforward “good idea” might spring to mind. But then, it’s almost certain that many others (including experts) have already tried and discovered how that “good idea” can’t work.

Much of the trouble with considering such systems is because of the human brain. It’s used to seeing direct results in causal or cause-effect chains; “If I do X, Y happens.” Evolutionarily, we humans are designed to understand simple causes and immediate results: We throw a rock, and we see it fall to the ground. On the other hand, complex socio-technical systems such as climate change are hard to understand because the human mind is not designed to understand something that complex. In design, we’re used to having the convenience of getting feedback through, for example, usability testing. But the human brain can’t understand the complexities of world systems. Take recycling, for example; many people have grown used to considering it more in terms of collective responsibility. However, we’re not used to thinking on a grander scale in terms of the many — often invisible — ways our environment reacts to the effects of our actions, purchasing choices and habits. Complex socio-technical systems are difficult to analyze because:

Many systems have several feedback loops. When you do something, result A might not appear but instead impact something else you can’t perceive (result B) and then affect other things. Only when a threshold is crossed might the first result you notice appear (e.g., result J).

There could be a long delay between triggering actions and the first noticeable results. Sometimes, so much time might pass that causes are only traceable through deep investigation and systems analysis.

This complexity is why Norman points the way to 21st century design and humanity-centered design. When we’re facing highly involved, massively-scaled human problems enmeshed in complex systems, we can’t use the same approach we might take for, say, an app (e.g., using design thinking alone).

We’ll never be able to solve some problems plaguing our world. How could we even tell if world peace occurred, for example? Still, we can do something to at least improve matters from one situation/project to the next and improve the world in little sections. Namely, we can leverage humanity-centered design to:

Use people-centered design to tap a population’s insights and keep them invested.

Solve the right problem, after in-depth consideration and (e.g.) using the 5 Whys method.

See everything as a system, and use systems thinking.

Take small and simple steps towards sustainable design solutions. Specifically, incremental modular design or incrementalism.

Big problems demand big solutions, but big solutions are too expensive, disruptive and prone to failure. Be pragmatic and “go small."

Once you understand the people you want to help, their situation’s realities and what their environment lets them do, wait for an opportunity to do something small but helpful. Then, see if it works well enough to either repeat/duplicate or improve. If it fails, it’s still small enough that it won’t spell disaster. Learn from it and use that knowledge to shape something that will work.

Small steps will also be more likely to win the community’s support. They happen quickly enough for people to see these aren’t hollow promises, and can even provide life-saving results. Success breeds success. If a small step leads to more victories, you’ll win even more community support.

Small steps taken at the right time can lead to the “best solution possible” at any future point — in contrast to a “big fix” taking (e.g.) 10 years, when the whole situation, including the nature of the problem will have changed.

Overall, be sure to work with the community leaders every step of the way.

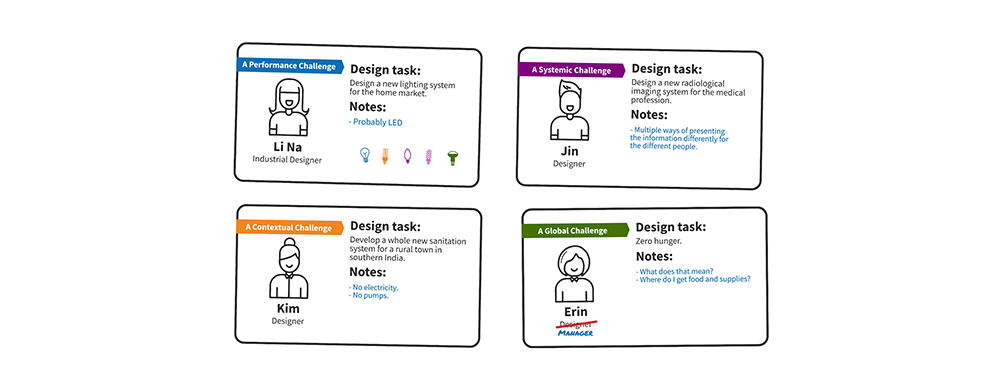

The four principles of Human-Centered Design are People-Centered, Solve the Right Problem, Everything is a System, and Small & Simple Interventions.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ready to shape the future, not just watch it happen? Join the Father of UX Design, Don Norman, in his two courses, Design for the 21st Century and Design for a Better World, and turn your care for people and the planet into design skills that elevate your impact, your confidence, and your career.

Norman, Donald A. Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2023.

Complex socio-technical systems involve many interconnected parts—people, technology, rules, and environments—that all influence each other. Unlike simple systems, where one action leads to one predictable result, complex systems behave unpredictably. In UX (user experience) design, this means a change to one element—like a user interface—can ripple through the whole system in unexpected ways.

These systems adapt, evolve, and depend heavily on human behavior and context. Think of a healthcare platform or a public transport app: designers must account for technical reliability and human workflows, regulations, and diverse user needs. You can't treat these systems like linear tools. Instead, UX designers need to observe real-world use, test iteratively, and design for flexibility. Understanding complexity helps designers build systems that are resilient, user-centered, and ready for real-life unpredictability.

Get a greater understanding of what designers must do with systems in our article Which Skills Does a 21st Century Designer Need to Possess?.

A system becomes “complex” in UX and product design when it has many interconnected parts—users, technologies, rules, and environments—that constantly interact and affect each other. These systems don’t behave in a straight line; small changes can trigger significant, unexpected outcomes. For designers, complexity means they can’t rely on one-size-fits-all solutions or assume users will follow predictable paths. Think of a smart home system or enterprise software with multiple user roles—designers must support varied goals, workflows, and contexts.

Complex systems often evolve over time, so good UX design must adapt, scale, and stay intuitive under changing conditions. What makes them truly complex is that no single person fully controls them. Designers must understand how people use these systems in real life—and design for flexibility, learning, and ongoing feedback.

Explore the wider realm of “complex” systems and what they mean for design in our Master Class Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman, Founding Director - Design Lab, University of California, San Diego. Co-Founder, Nielsen Norman Group.

UX designers should care about the social side of technical systems because technology doesn’t exist in a vacuum—people use it within social, cultural, and organizational contexts. A design that works perfectly in isolation might fail when real people, power dynamics, or team workflows come into play. For example, a project management tool might look user-friendly, but people won't use it effectively if it doesn’t support team norms or leadership styles.

The social side shapes trust, communication, and adoption. Designers who ignore it risk building systems that frustrate or exclude users. UX designers can create tools that truly support human goals by understanding the social context—how people collaborate, make decisions, or share information. This leads to more inclusive, effective, and sustainable products that people will want to use and keep using.

Discover vital points about how to design with culture in mind, in this video with Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Copyright holder: Tommi Vainikainen _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Copyright holder: Maik Meid _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Norge_93.jpg

Copyright holder: Paju _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kaivokselan_kaivokset_kyltti.jpg

Copyright holder: Tiia Monto _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Turku_-_harbour_sign.jpg

Socio-technical systems show up everywhere in daily life—anywhere people and technology work together. Think of public transportation apps like Citymapper or Google Maps. They don’t just deliver data; they coordinate real-time traffic, city infrastructure, and user decisions.

Online banking is another example; it blends secure software, government regulations, financial institutions, and user trust. Even a food delivery platform like Uber Eats relies on complex interactions between customers, drivers, restaurants, GPS systems, and payment networks.

These systems can’t succeed on technology alone; they need to support how people communicate, make choices, and solve problems. For UX designers, recognizing these everyday socio-technical systems means understanding that user experience is shaped not just by screens and flows, but by the broader social and organizational context that surrounds the product as well.

Explore the nature of 21st-century design to understand more about what designing for complex systems involves and tips on how to find solid answers to harder-to-spot issues.

The biggest UX challenges in complex socio-technical systems come from their unpredictability and human complexity. Designers can’t control how every part of the system behaves—users, technologies, rules, and organizations all influence each other. That makes it hard to map user journeys or predict outcomes. One major challenge is designing for diverse user roles with competing goals, like in healthcare or enterprise software.

Another is ensuring the system stays usable as it evolves. Misaligned incentives, outdated workflows, or poor stakeholder communication can also break the user experience. Testing in real-world conditions becomes crucial, but difficult. Designers must stay flexible, focus on adaptability, and keep collecting feedback. In these systems, great UX isn’t about perfection but resilience, inclusivity, and supporting people through complexity.

Explore what user journeys involve in our article Top Tips to Create Effective Journey Maps.

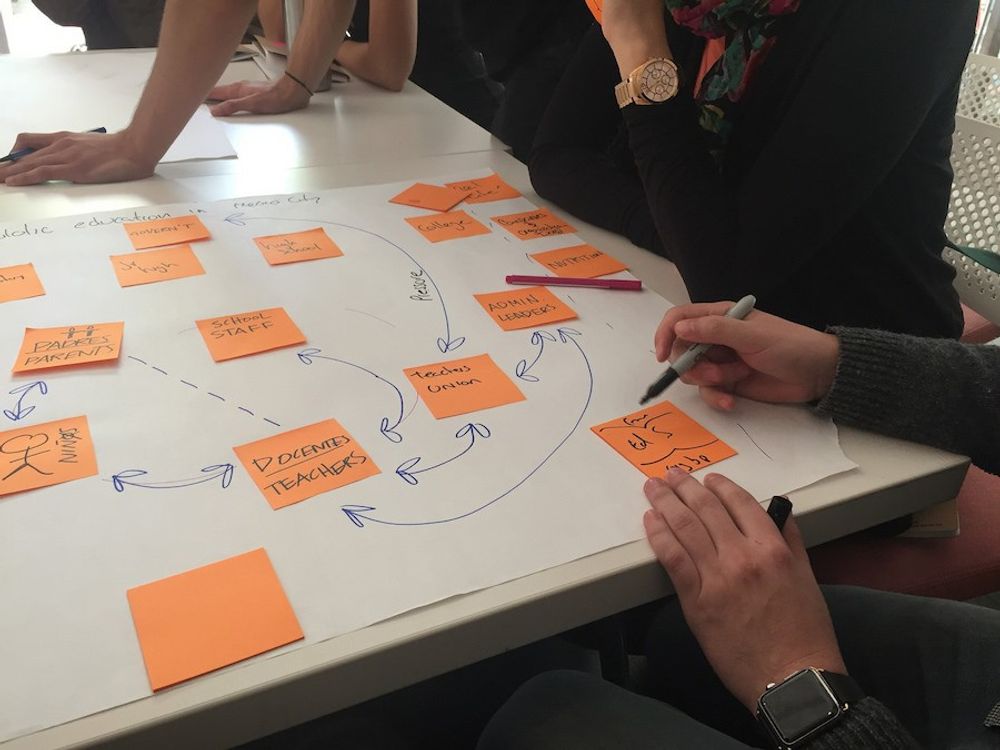

Systems thinking is essential for UX and product designers because it helps them see the bigger picture—how parts of a product connect, influence each other, and affect the user experience over time. Without it, designers might fix one issue while accidentally causing another.

One design decision can impact workflows, policies, and user relationships in complex environments like healthcare, education, or enterprise tools. Systems thinking encourages designers to go beyond screens and consider user goals, team dynamics, tech constraints, and long-term effects. It helps identify root problems, not just surface symptoms. This approach leads to more thoughtful, flexible, and scalable designs. By thinking in systems, designers can build products that fit into real-world contexts and support users across changing needs and conditions.

Discover how to uncover root problems using the 5 Whys technique.

Designers identify breakdown points in complex systems by observing how users interact with the product in real-world contexts. They look for moments where users get stuck, work around the system, or switch to other tools. These signs often reveal where the system doesn’t align with real workflows, expectations, or communication patterns. Interviews, usability testing, and journey mapping help surface these gaps, especially when designers involve users from different roles or environments.

Logs, support tickets, and usage data highlight where things go wrong. In complex systems, breakdowns aren’t always bugs; they can come from unclear processes, conflicting goals, or poor integration with other tools. By spotting these friction points, designers can improve the system’s flow, reliability, and user trust, often by simplifying interactions or better supporting collaboration.

Explore one helpful approach to learn how users encounter design solutions and much more, via ethnographic research.

Designing for socio-technical environments requires a people-first approach that considers both technology and the social context around it. Start by involving diverse users early—people from different roles, teams, and backgrounds—so you understand how they use the system.

Map out workflows, communication patterns, and decision points to uncover hidden needs or constraints. Build flexibility into the design, since these systems often evolve and vary across settings. Support collaboration by making actions transparent and shared across users.

Always test in real-world scenarios, not just ideal ones, to catch friction points that only appear in context. Keep feedback loops open; effective socio-technical design adapts over time. Most importantly, respect the human side: trust, culture, and relationships shape how people use tools, so the design should empower, not frustrate, those interactions.

Find out more about feedback loops and what designers do with them.

To reduce cognitive load in complex systems, designers must simplify tasks, not just screens. Group related actions together and break long processes into clear, manageable steps. Use progressive disclosure; show users only what they need at the moment, not everything at once. Make labels, instructions, and icons clear and consistent so users don’t sink mental energy into needless guessing.

Support recognition over recall by offering suggestions, autofill, or visible options. Visual hierarchy, white space, and familiar patterns help users focus on what’s important. Show feedback clearly, too, as users must know what’s happening and why. When users feel confident and not overwhelmed, they navigate even complex systems more easily. In high-stakes areas like healthcare or logistics, these strategies aren’t just nice; they’re essential for safety, efficiency, and trust.

Find out why recognition vs recall is a vital rule in UX design and how designers help users with it.

To help your team think beyond screens and features, shift the focus to user goals, workflows, and real-world outcomes. Start by framing problems regarding what users need to achieve, not what UI to build. Use journey maps, service blueprints, and stakeholder interviews to highlight how design fits into broader systems.

Encourage the team to consider offline touchpoints, organizational processes, and emotional states that affect user experience. Run workshops that explore “a day in the life” of users or map end-to-end service flows. Ask questions like, “What happens before and after this screen?” or “What if this feature did not exist?” These prompts help the team see the full context. Designers can create smarter, more meaningful products when they connect features to user behavior, team goals, and business impact.

Check out what goes into a service blueprint and why it is useful, in this video concerning a popular brand with Frank Spillers: Service Designer, Founder and CEO of Experience Dynamics.

To test a socio-technical system’s user experience, evaluate how well the system supports real workflows, collaboration, and decision-making across different users and roles. Use field studies, contextual inquiries, and scenario-based testing to observe how people interact with the system in real settings. Look for mismatches between the design and social dynamics, like confusion, workarounds, or communication breakdowns.

Involve a mix of users, especially those with different goals or authority levels, to uncover hidden friction points. Track how well the system supports tasks over time, not just in a single session. Collect both quantitative data (like task completion or error rates) and qualitative insights (like trust, stress, or satisfaction). A strong UX in these systems balances clarity, flexibility, and support for complex human relationships.

Explore the difference between quantitative and qualitative research—both vital ways to establish solid design foundations—in this video with William Hudson: User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd.

Norman, D. A., & Stappers, P. J. (2015). DesignX: Design and complex sociotechnical systems. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 1(2), 83–94.

This paper introduces "DesignX," a framework addressing the challenges of designing complex sociotechnical systems. Norman and Stappers argue that traditional design methods fall short when tackling large-scale, interconnected systems like healthcare or transportation. They advocate for a shift towards systemic design approaches that consider the intricate interplay between technology and social factors. For UX designers, this work underscores the importance of holistic thinking and the need to engage with broader system dynamics beyond user interfaces.

Norman, D. A. (2023). Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered. MIT Press.

In this book, Norman expands on the concept of humanity-centered design, advocating for design practices that address global challenges and promote sustainability. He emphasizes the role of designers in shaping a better world by considering the broader impacts of their work. For UX designers, the book serves as a call to action to engage with complex socio-technical issues and to design solutions that are ethical, inclusive, and sustainable.

Lucidchart. (2023). The importance of sociotechnical systems. https://www.lucidchart.com/blog/sociotechnical-systems

Lucidchart's blog post explores the concept of sociotechnical systems and their significance in modern organizations. It discusses how aligning technological solutions with human and organizational needs can enhance system effectiveness. The article offers practical examples and considerations for UX designers aiming to create systems that are both technically robust and socially attuned.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Complex Socio-Technical Systems by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Complex Socio-Technical Systems with our course Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your expert for this course:

Don Norman: Father of User Experience (UX) Design, author of the legendary book “The Design of Everyday Things,” co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group, and former VP of the Advanced Technology Group of Apple.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!