Three Common Models of the Brain to Help You Develop Better User Experiences

- 752 shares

- 5 years ago

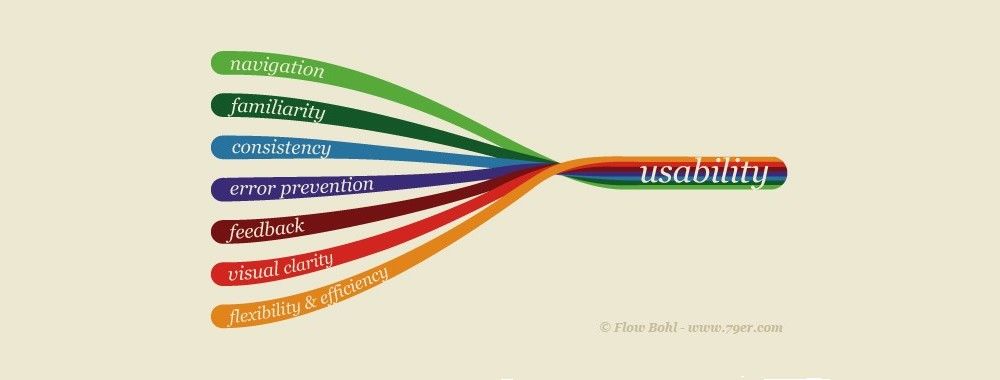

Mental models are internal representations users form based on past experiences and understanding. These models shape how people expect systems and interfaces to behave. UX (user experience) designers analyze and accommodate these expectations to create intuitive, user-friendly digital experiences that minimize confusion and increase usability.

“Users spend most of their time on other sites. This means that users prefer your site to work the same way as all the other sites they already know.”

— Jakob’s Law (Jakob Nielsen, Usability Pioneer and Co-founder of the Nielsen-Norman Group)

Humans rely on mental models to make sense of a complex world and have done so long before the advent of digital products. For example, a map simplifies a physical space, such as a country, into a visual representation for people who use it to understand where cities, towns, villages, forests, rivers, lakes, and other geographical features are—and how to get from A to B. As vital points of reference for decision-making, problem-solving, and learning, such models of the mind save people from having to learn from scratch every time they encounter an item, system, or concept. They’re also essential when individuals must communicate concepts to others, as a flexible and informal “knowledge base” for everyone to refer to.

In UX design, a mental model refers to what a user believes about how a system works. This belief system guides how users interact with a product, form expectations, and interpret feedback from the interface. These models often come from previous experiences with similar systems, cultural norms, and learned behaviors. Being human, users like to act on assumptions; it helps them push through uncertainty and do what they need or want to do more efficiently—if their assumptions and mental models are correct.

Google Maps taps into users’ mental models of physical maps but adds helpful details such as pictures and business hours. Interestingly, libraries were once the dominant mental model for information searches—for example, before one could “Google” (as a verb) a subject.

© Google, Fair use

The rise of home computing in the 1980s and the World Wide Web in the 1990s ushered in the Digital Age, or Information Age, which is maturing such that smartphones are currently the “dominant” means of interaction. To help users enjoy more seamless experiences, early designers leveraged skeuomorphism—a design style that features real-world elements. For example, most users understand that a magnifying glass icon symbolizes “search.” That association forms a mental model; users expect that clicking the icon will let them look for something. Similarly, they expect a trash can or recycling bin icon to indicate deleted content, and a shopping cart to represent items stored for purchase soon after those goods enter the cart.

Users don’t need to know how the underlying systems function technically. What matters is their ability to predict outcomes based on familiar cues.

1. They Shape User Behavior

A mental model is what the user believes about the system in question—including how it behaves, what they can do with it, and what will change in the system if they take certain actions. This belief influences every interaction a user may have. Whether those beliefs are accurate or not, designers must consider carefully how to accommodate and respond to them. When a product aligns with users’ expectations, it feels easy to use. When it doesn’t, users become confused or frustrated.

For example, most users understand that a shopping cart or basket icon signals “items I’ll buy later.” They also know a trashcan or a recycling bin is where their deleted items are held until they choose to empty the container. However, what about a magnifying glass? Arguably, users could identify microscopes, compasses, binoculars, telescopes, and even tracker dogs as good items to search with. While trash versus recycling bins might be a matter of ecological preference, the magnifying glass is the item from the “analogue” world that means “search” in the digital world. Even though a magnifying glass takes on a slightly different functionality in, for example, Adobe software where users use it to zoom in and out, it also functions in Acrobat for users to search for text with.

2. Mental Models Drive First Impressions

Users bring their mental models to a product from the first moment they see it. These impressions affect whether users stay, engage, and succeed, or quit and possibly go to a competitor’s website or application. Users’ first impressions form in milliseconds for digital solutions like websites and apps. A mismatch between user expectations and interface behavior leads to errors, abandoned sessions, or support requests.

For example, a new website might confuse users due to something as simple as a misunderstood “shopping bag” instead of a cart or basket. The brand might have an “eco-friendly” identity and prefers to offer its customers an icon of what appears to be a hemp net bag instead of a (potentially plastic or metal) cart or basket to put their intended purchases in. However, if they also label it as “Shopping bag,” most users will understand a bag to be what they take their shopping items away in after they’ve purchased them. That mismatch could cost the brand many potential customers.

I remember shopping on an e-commerce site for a hardware store that sold tools and garden equipment, and they called their shopping cart a “wheelbarrow.” Sure, that’s cute and all, but most web shoppers are familiar with the shopping cart metaphor. When they are finished shopping and are ready to check out, they will scan your site looking for the cart so they can complete their purchase, but if all they see is “wheelbarrow,” there’s always the chance that a few of them will get confused about what they are looking for. Hardware stores don’t give you a wheelbarrow to shop with, so why should we get creative with an online storefront anyway? If you want to detract from the usual name and go with something a little more quaint, I believe that “basket” is a close second choice to “shopping cart.”

— Jim McGaw, Beginning Django E-Commerce (Apress, 2009)

Users’ mental models apply internationally, too; for example, in France, Amazon buyers can add items to a cart icon labeled “Panier” (“Basket”), conforming to the users’ mental model of where their intended purchases are kept.

© Amazon.fr, Fair use

3. They Influence Learning

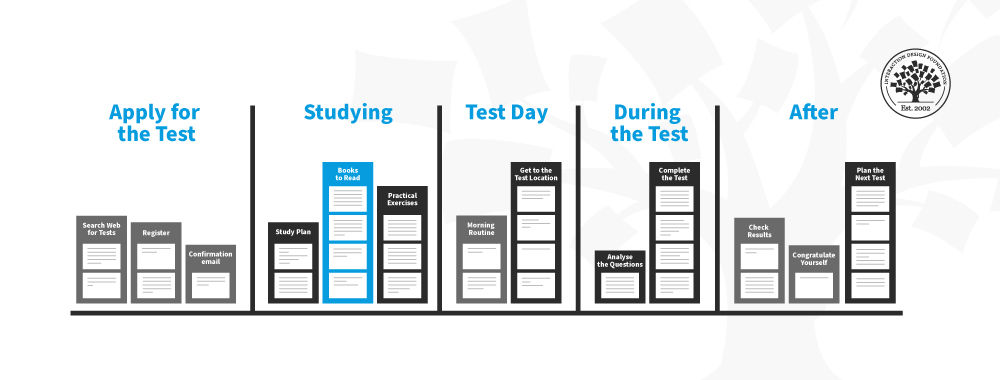

According to a significant academic paper on mental models—Kieras and Bovair’s 1984 research piece, The Role of a Mental Model in Learning to Operate a Device—users learn and operate devices more efficiently when they hold accurate mental models than if they learn about a device’s operation by memorizing instructions. When models are incomplete or incorrect, users struggle to understand cause and effect and make performance errors. This finding reinforces the value of aligning system design with user expectations—not just for usability, but also for learnability.

Users, like students, learn more meaningfully when the systems and features of systems they encounter conform to their mental models of how such things should operate. However, what about more complex systems that require intricate features for users to complete tasks with them?

For example, consider two claim management systems (CMS, or claims processing systems) that two designers might create for their respective client companies. In this case, it could be for workers at brands that offer insurance services. Both companies have just hired many new customer-service representatives who must handle customers’ car and building damage and injury claims and process these on the new systems. One CMS is more complex than the other and presents users with a massive group of dropdown menus, tabs, and more than one search field on a single page.

The other CMS, however, features a system design that has greater usability and learnability. For example, users can click over a map feature to locate repair shops, and the designer has applied progressive disclosure so they can easily find more specialized items—such as more complex insurance handling procedures—only if they need to access that screen due to the customer’s need.

Both that CMS and the more complex one offer the same (theoretical) level of functionality to their users. The difference will show in the error rate, confusion and frustration levels, and—if the first system is bad enough—how many workers complain or even quit.

Explore how progressive disclosure helps users enjoy more successful designs, in this video with William Hudson: User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd.

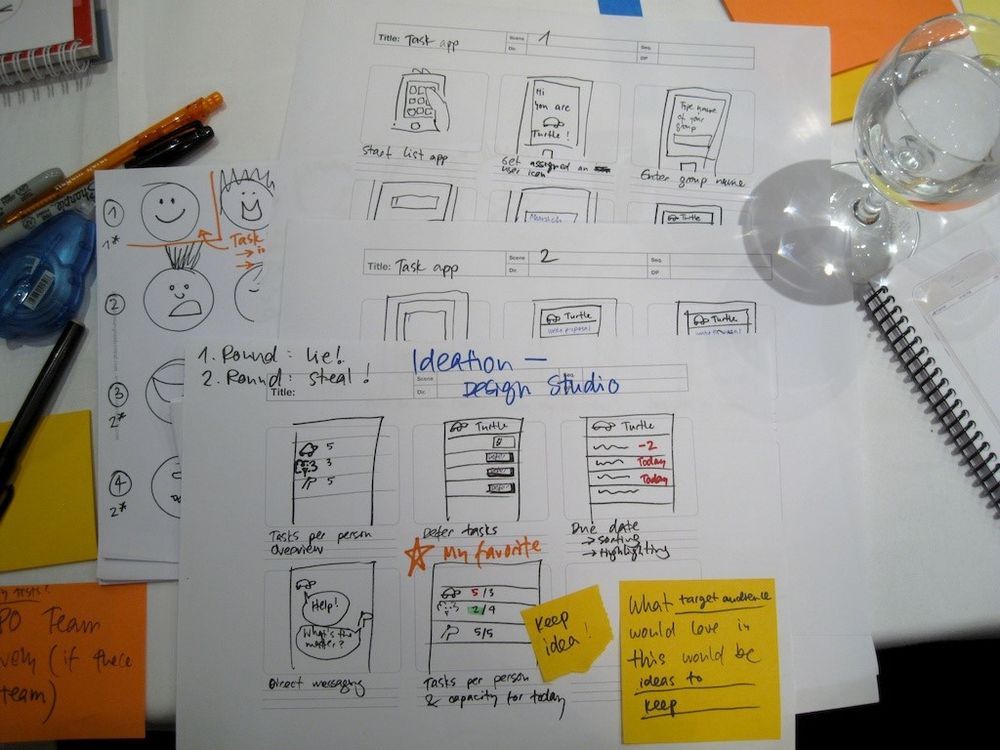

Start by learning what users believe about systems like yours or the one you’re intending to design. Use approaches such as:

User interviews and contextual inquiries: Ask users how they expect things to work and why. For contextual inquiries, you observe users in their natural environment to understand their contexts and workflow—and examine what mental models they might have about a solution or potential solution to help them perform tasks and achieve goals.

Explore considerations and valuable tips about user interviews in this video with Ann Blandford: Professor of Human-Computer Interaction at University College London.

Card sorting: One of the most useful tools for mapping mental models, card sorting helps identify how users categorize concepts. This data informs navigation design and page grouping.

Discover important points about what sort of card sort content can help most, in this video with Donna Spencer, Author, Speaker and Design Consultant.

Tree testing: A tree test simulates a hierarchical navigation structure and helps designers align and structure websites and the like with how users think.

Try tree testing to find out important insights about users’ expectations, as this video with William Hudson discusses.

Analyze what you gathered in your user research to uncover how users mentally model your product or system. This step involves identifying shared assumptions, expectations, and terminology, as well as pinpointing any disconnects between what users believe and how you intended your system to function.

Start by coding qualitative responses from interviews or open-ended survey questions. Look for recurring language, metaphors, or expectations. For example, do several users expect to find billing under “Settings”? Do they refer to “saving” when there’s no save function, as in Google Docs? These patterns reveal how people mentally structure your product.

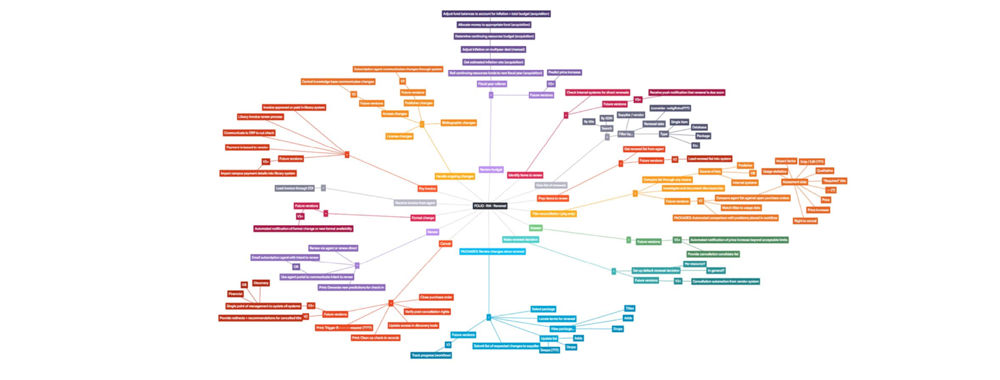

For card sorting data, tree analysis done in the form of a dendrogram can be helpful.

Identify mismatches and flag areas where user expectations diverge from your system model. For example, users might expect a “back” button to take them to the previous content view, but your app returns them to a homepage. These discrepancies are red flags for usability friction.

Mismatches aren’t just usability issues or minor slips—they’re cognitive mismatches. They often cause problems or hesitation because users must pause to re-evaluate how things work, which increases cognitive load. They also break what could otherwise be a seamless experience with your product and brand.

Mental models in this popular music app include how users can find album covers and song listings—as older users would recognize from the days of vinyl LPs—and play them using the universally understood Play button.

© Spotify, Fair use

Create interfaces that reflect common expectations. Use metaphors, icons, and flows that users already understand. For example, if they can save their work, does “save” mean they expect to find a floppy disk icon? Use prototypes and test them with users. Prototyping offers an essential and cost-saving way to create early versions of proposed solutions and test assumptions.

Find out how prototyping helps fast-track more successful designs, in this video with Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

It’s important to keep in line with users’ mental models about how they accomplish tasks—such as finding music, eating out, or buying a house. The music example (in the images above) is relatively simple.

Eating Out: A Mirror of Familiar Steps

Dining apps reflect the predictable flow of eating out: choose food, browse options, order, and then confirm. Uber Eats and OpenTable are examples of apps that follow this sequence with clear categories, intuitive filters, and visual menus. Features like availability indicators or delivery tracking simulate real-world cues, making the process seamless.

Buying a House: A Guide to a Complex Journey

Home-buying apps support a longer, multi-phase process: search, evaluate, plan finances, and act. Take an app like Zillow: using maps, photos, and calculators to match how buyers explore neighborhoods and assess affordability. Tools like saved searches and tour schedulers mirror real-world next steps, keep users oriented and progressing, and can be great sources of help during what can be a stressful, if exciting, time.

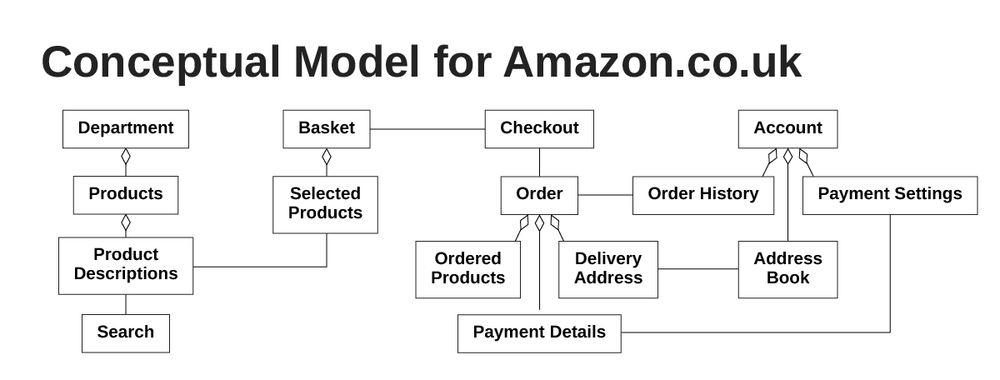

Mental models heavily influence information architecture (IA). If users expect “Billing” and “Payments” to be in the same menu, keep them together or users may become confused. Use your card sorting results and user feedback to create an IA that matches real-world logic—not just internal business logic.

Understand more about how to structure an effective information architecture from this video.

Fortunately, designers have a strong “ally” in the form of competitive analysis. You can select your problem domain, find the key players, and observe what they do to provide solutions and mark some important points to work with.

Familiarity is key as far as you can apply it to help users. However, when you must diverge from familiar patterns, help users adjust. Tooltips, onboarding flows, FAQs, and contextual help can close the gap between the system model and the user’s mental model.

Be proactive. Think of documentation not as an afterthought but as an essential layer of the user experience—particularly where your product breaks from convention. If what users find on the screen empowers them to intuitively interact with your brand for most tasks and purposes, it’s a healthy sign. It can mean that for instances where they must stretch beyond their comfort zone, at least they should trust your design enough to accommodate any adaptations they must make in their mental models.

Speaking of comfort, one vital consideration is that you understand the users’ contexts of use. Users will “arrive” on your digital product in a variety of situations. Remember the front-line insurance workers? Imagine their user contexts: often high-stress customer complaints, frequently high-value property damage, always the need to focus on precise actions. Users’ mental models don’t help them in a vacuum; they need empathic designers to help them apply those models in the moment.

Dig deeper into user contexts to learn why it’s vital to design for them, in this video with Alan Dix.

Respect familiarity: Unless innovation offers clear user benefits, default to common metaphors and conventions—such as the magnifying glass for searches.

Support learning: When diverging from norms, help users form accurate new models with guidance and repetition.

Test and iterate, continually: The only way to validate users’ mental models is to observe real users in action. Ask them to think out loud as they encounter and try to use prototypes, for example. Note what they do and say.

Design for change: Expect users to bring prior assumptions and allow your interface to gently reshape those over time. For example, the floppy disk is still around for “save,” but it may not be in the future.

Understand mental model inertia: Change is difficult. Users will naturally resist changing their internal expectations—even when those expectations are outdated or inaccurate. For example, people who learned to save documents by clicking a floppy disk icon may still expect that metaphor, even though physical disks are obsolete, and the number of users who did use those disks will dwindle as time ticks on. That’s mental model inertia in action.

Create reliable user personas: These fictitious representations of real users help designers fine-tune what they include in websites, apps, and other solutions according to the real-world needs and behaviors of the individuals who will use them. Personas can help inform design choices with vital considerations about many factors, including contexts and mental models.

Find out why personas are not only helpful but essential parts of design, too, in this video with William Hudson:

Design tooltips, onboarding, and FAQs to correct misconceptions.

Use clear visual cues and feedback to guide user behavior.

Support findability and discoverability: For example, the hamburger menu might align with users’ grasp of what to click to find more options, but it hides content they need there and then. Consider the users’ in-the-moment needs.

Anticipate misunderstandings before they happen. Where are users likely to make slips, errors, or mistakes? Simple errors may happen in an imperfect world, but mistakes that arise from disconnects between a user’s mental model and your design are serious red flags. Expert or heuristic evaluations can help catch these and other problems.

Explore how a heuristic evaluation can safety-ledge areas where your design might otherwise fall, in this video with William Hudson.

Conduct regular usability testing to keep up with evolving expectations. Test, test, and test again over time to determine how well it accommodates users’ mental models.

Not all mismatches carry the same weight. Focus your redesign efforts on gaps that affect core tasks or cause frequent user complaints. For example, if a small navigation label misleads users consistently, fixing it may yield greater usability gains than rethinking a rarely-used feature. However, a disconnect between how a user expects a delete function to work and the result that an item they decide to keep isn’t retrievable can be far more serious. Deleting something fully should take two “hits”; the first one should send it to the (holding) bin.

Users who remember what it was like to book vacations “back in the day” can relate to a host (no pun intended) of conveniences and effective tapping of mental models with Airbnb. There’s the hotel-like booking experience with destination input field, date-pickers, and number of guests. However, Airbnb elevates this to a new level with an informal “staying at a friend’s” vibe while building the same level of trust that, for example, 1970s’ holidaymakers would have expected from a reputable travel agent.

© Airbnb, Fair use

Overall, mental models shape how users think, behave, and learn in the face of an uncertain world. People create and use mental models involuntarily. However, the larger concern is inappropriate or inconsistent mental models; for example, people commonly associate some effect with the incorrect cause. If users develop the wrong mental model of your product, it will become harder to use, no matter how functional the backend is.

Designers who take the time to confirm their assumptions about their users’ assumptions and more can save their users much frustration and confusion. They can also help reduce their brands’ support costs and abandonment rates. Experiences that feel natural, trustworthy, and efficient revolve around screens and other designed items that align with how users understand things should work.

In our complex and subjective world, users bring diverse perspectives, cultural backgrounds, and individual quirks to every digital interaction. Whenever people encounter new platforms, apps, or brand experiences, they rely on their existing mental models to navigate unfamiliar territory. Designers can help by creating interfaces that align with these mental models, translating complex functionality into intuitive, seamless experiences that feel natural and effortless to use.

Learn how to use Mental Models in Mobile UX.

Read more about the importance of mental models in decision-making and critical thinking, using Charlie Munger's approach as an example.

Discover how to create user-friendly designs that align with users' mental models by applying Jakob's Law.

Don’t miss this excellent masterclass to learn How To Design For The Way Your Users Think.

Learn about mental models and their role in user experience design in this informative article.

Read more about transforming Mental Models into Conceptual Models for Mobile UX.

A mental model in UX (user experience) design is the way users think something works, based on past experiences, habits, or expectations. It’s their internal blueprint for interacting with a product. When the design matches that mental model, users navigate easily. However, when it doesn’t, confusion and frustration follow.

Good UX aligns with users’ mental models. For example, people expect a shopping cart icon to hold selected items they’ll purchase at some point soon. Changing that pattern, not matter how “innovative” or “cool” that may seem, will create unnecessary friction for most users.

Explore one aspect of designing for users’ mental models in our article Embrace the Mental Models of Users by Implementing Tabs.

Mental models matter in user experience design because they shape how users interpret, navigate, and interact with digital products. When a design aligns with a user’s mental model, they feel in control, confident, and successful. However, when there’s a mismatch, confusion sets in, leading to errors, drop-offs, or frustration.

Designers who understand mental models can create intuitive interfaces that “just make sense.” This reduces learning curves and improves usability. They know not to design based on how they think something works but rather to design based on how their users believe it should work. Research is the key to uncovering their expectations, before testing to validate alignment.

Explore the vast realm of user research to find vital insights and tips on how to start off any design project properly.

To identify mismatches between user mental models and your design, observe where users hesitate, make mistakes, or ask, “What now?” These moments reveal gaps between what users expect and what the interface actually does. Think-aloud testing, usability studies, and journey mapping are powerful tools to spot those disconnects.

For example, if users click a logo expecting to return to the homepage, only to find that it doesn’t, they’re operating on a mental model your design fails to support.

Tip: Ask users to explain what they think will happen before they act. Compare their expectations to what your product actually delivers. This reveals key design mismatches fast.

For navigation structures like menus, users’ success or failure in reaching a goal can be tracked in detail using tree testing. Take our course on quantitative UX research to discover more.

Cultural and generational differences shape mental models by influencing what users expect, value, and understand. For instance, older users may associate saving files with a floppy disk icon; many of them will recall using floppies in 20th-century computers. However, younger users—many of whom have never seen let alone used a floppy disk—might not recognize its meaning. Likewise, users from different cultures may interpret gestures, colors, or navigation patterns differently.

These variations can cause confusion if a design assumes a “universal” model. To create inclusive UX, designers must research how diverse user groups perceive and interact with digital products.

Tip: Test your design with a variety of users. Look for patterns across age groups and cultural backgrounds to spot mismatched assumptions early.

Take a fresh look at assumptions to see what problems they can cause in design and how to work well with them.

To design interfaces that match user mental models, start by understanding how your users expect things to work. Use interviews, task analyses, and usability tests to uncover their assumptions. Then, structure your interface to align with those expectations, especially around layout, labels, navigation, and feedback.

For example, if users expect a magnifying glass icon to mean “search,” which they should, using anything else adds friction, even if it might make sense to your design team (for example, a microscope). When your design behaves the way users think it should, you create intuitive, frustration-free experiences and nobody will dislike it for “trying to be smart.”

Tip: Match mental models, don’t fight them. Use familiar design patterns unless you have a strong, tested reason to introduce something new.

Empower your design team to provide users with what they expect and delight them in the process by leveraging user interviews optimally.

To create onboarding experiences that shape better mental models, design clear, guided introductions that show users how and why things work the way they do. Don’t overload new users with features—help them form accurate expectations through simple tasks, tooltips, and contextual cues.

Onboarding should mirror real workflows so users build the right mental connections. For example, showing how to post a message in a chat app reinforces where conversations live and how threads behave; users can map out an accurate picture of the wider process.

Tip: Use progressive disclosure. Reveal complexity as users need it, not all at once, so they develop mental models step by step, with confidence.

Find out how to use progressive disclosure to your advantage and keep more users on board as they learn things when they’re ready to.

Familiar UI patterns support existing mental models by matching what users already know, making interactions faster and more intuitive. When users see a trash can icon, they expect to delete something. Despite a few hiccups with hamburger menus, a hamburger icon generally signals navigation. These patterns reduce the learning curve and help users feel confident from the first click.

By reusing proven conventions, designers tap into mental shortcuts users have formed over time. This speeds up decision-making and minimizes frustration.

Tip: Stick with widely recognized patterns unless you have a clear, tested reason to break them. Innovation is great—but not at the cost of usability.

Understand how UI design patterns help more users enjoy more easy-to-use design solutions, from this brief video:

To simplify complex tasks, design flows that match how users think the task works—not how the system operates. Mental models guide users’ expectations. When your UX design follows those expectations, even complex actions feel easy.

Break big tasks into smaller, familiar steps. Use labels, icons, and layouts that mirror users’ mental blueprints. For example, if someone books a flight, they expect to select dates, destinations, and passengers using features like date pickers—so match that mental model in your UI.

Tip: Observe real users performing the task offline or in competitor tools. Use those insights to align your flow with their natural process.

Stay a step or two ahead of users when you know How to Use Mental Models in UX Design.

When users have no prior mental model of your product, your design must build one from scratch—clearly, gently, and step by step. Start with intuitive onboarding that explains core concepts through action, not just instruction. Use visual cues, tooltips, and guided interactions to help users form accurate expectations.

Prioritize clarity and leave out jargon. Structure tasks in a logical sequence, and reinforce correct use with immediate feedback. When users take the right action, confirm it clearly; this helps shape their understanding.

Tip: Watch where first-time users struggle. Use that insight to improve affordances and guide users toward the mental model your product needs them to adopt.

Open the door wider for ideas to get through by understanding how affordances work.

Full Clarity. (n.d.). Mental models in UX design: Understanding user expectations. Full Clarity.

This article explores the concept of mental models and their critical role in UX design. It highlights how users' expectations, shaped by their experiences, influence their interaction with digital products. The piece underscores the importance of aligning design with these mental models to create intuitive and user-friendly interfaces. It also discusses challenges in identifying users' mental models and offers strategies for testing and validating design decisions to ensure they meet user expectations.

Hunt, W. (2023, May 2). 10 examples of mental models in UX design. Deliverable UX.

Hunt presents ten practical examples of mental models in UX design, illustrating how users' expectations influence their interaction with interfaces. The article discusses common UI elements, such as the hamburger menu and back/forward buttons, and how they align with users' mental models to facilitate intuitive navigation. By understanding these models, designers can create more user-friendly designs that meet users' expectations and improve overall usability.

Hudson, W. (n.d.). Mental models, metaphor, and design. Syntagm.

Hudson explores the relationship between mental models, metaphors, and design, highlighting how metaphors can help users understand complex systems by relating them to familiar concepts. The article discusses the role of mental models in user interaction and how designers can leverage metaphors to align interfaces with users' expectations. By understanding and designing for users' mental models, designers can create more intuitive and effective user experiences.

Young, I. (2008). Mental Models: Aligning Design Strategy with Human Behavior. Rosenfeld Media.

Indi Young's seminal work introduces a methodology for understanding users' thought processes to inform design decisions. By constructing mental models, designers can align their strategies with actual user behaviors and needs. The book provides step-by-step guidance on conducting user research, analyzing data, and creating mental model diagrams. It's a valuable resource for UX professionals seeking to ground their designs in a deep understanding of user motivations and tasks.

Norman, D. A. (2013). The Design of Everyday Things (Revised and expanded ed.). Basic Books.

Don Norman's classic text explores the psychology behind how users interact with products, emphasizing the importance of aligning design with users' mental models. He introduces concepts like affordances and signifiers, which help designers create intuitive interfaces that match user expectations. This book is foundational for understanding the principles of user-centered design and the role of mental models in creating effective user experiences.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Mental Models by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Mental Models with our course Mobile UX Strategy: How to Build Successful Products .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your experts for this course:

Frank Spillers: Service Designer and Founder and CEO of Experience Dynamics.

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Torrey Podmajersky: Author of “Strategic Writing for UX” and President of Catbird Content, who has designed and executed content strategies for iconic brands like Google, OfferUp, and Microsoft.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!