What Science Can Teach You about Designing Great Graphical User Interface Animations

- 779 shares

- 5 years ago

Cognitive science is the discipline that explains how people perceive, remember, decide, and act. In UX (user experience) design, it turns guesswork into evidence when designers and researchers use insights about attention, memory, perception, and emotion to reduce effort for users, guide user decisions, and prevent errors. Teams craft interfaces that fit how minds work when they link research with practice.

Discover how cognition plays a vital role in everyday human lives and what it means for people as users, in this video with Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Cognitive science offers designers a toolkit of proven insights about how people think, remember, perceive, and act, which translate into concrete benefits for both users and product teams. Cognitive science UX design is where designers ground their efforts in the realities of how users think and act, instead of their own assumptions. More specifically, cognitive science principles help designers through key benefits and design practices as they:

Users can only hold about four “chunks” of information in their working memory at once. This is the part of short-term memory that handles immediate conscious linguistic and perceptual processing, and designers make sure UIs (user interfaces) don’t overload this limited capacity. For example, a well-designed airline booking form keeps all entered passenger details visible on the payment page so users don’t have to remember them while they’re completing payment.

UIs that show users their available options reduce the cognitive burden on users compared to making them remember possibilities from memory. For example, a navigation menu that displays all main sections instead of hiding them behind a generic “Menu” label lets users recognize rather than recall their options.

Cognitive load theory warns that too much complexity at once can overwhelm the mind and prevent users from completing tasks. Users might even abandon what they are trying to do altogether and then go to a competitor’s website, for instance. For an example of how designers address this, a multi-step checkout process reveals only relevant fields at each stage rather than showing everything at once—a tactic known as staged disclosure.

The Hick-Hyman law shows that the more choices people have, the longer it takes them to pick one. In UX design, as with any situation where individuals face a great number of options, they can become spoiled for choice—and, faced with “selection overload,” many of them may not even pick anything and leave instead. Designers therefore apply thoughtful constraints to help users progress faster. For example, a streaming service might show only a handful of movie categories on the home page, with a “See More” link for deeper exploration.

Amazon Prime Video’s approach offers viewers interested in action-adventure motion pictures a prime selection of entertainment, starting with top results, then “Based on your search” shows some personalization, and more (further down) to help users in their search of what to watch.

© Amazon, Fair use

The science of the brain relates to the hand as well. Fitts’ law explains why target size and distance matter for quick, accurate interaction—and larger targets that are closer to users’ focus points help them enjoy better performance. The alternative—smaller targets farther from these focal points can frustrate users and slow them down. For an example of Fitts’ law applied well, a mobile email app places its “Compose” button in the bottom-right corner, where most right-handed users’ thumbs naturally rest, and where users are used to finding this familiar design pattern.

This sphere of brain science also lends itself to the area of design principles and visual design—namely in how users respond to design factors such as shapes, sizes, and colors. It particularly accounts for certain phenomena, such as what the Gestalt principles—or Gestalt laws—address. The Gestalt School of Psychology dates to the 1920s, and its findings reveal how people instinctively group and interpret visual information through such laws as proximity, similarity, and closure.

For example, a banking dashboard groups account balances together and transaction history separately, a convenience that makes information scanning effortless for users.

Explore how to tap into the power of Gestalt principles to serve users more effective, pleasant-looking, and highly helpful designs, in our video.

Users expect systems to behave in familiar ways based on their previous experiences, and often this carries over from their understanding of how the physical world operates. For example, e-commerce sites use carts and baskets, mirroring “tools” from the “real” bricks-and-mortar store experience. Designs should match these expectations to reduce learning curves. For example, an e-commerce site places the shopping cart icon in the top-right corner, where users expect to find it, and marks it as a “cart.”

Users need to see what actions are possible (affordances) through clear visual indicators (signifiers)—which, like mental models, borrows from the physical world, such as a door with “PUSH” engraved on the push-plate. For a digital example, a button’s raised appearance and hover effects signal that users can click it.

See how to apply signifiers as vital guideposts in better designs which users can take to faster and in seamless experiences, in our video.

Users need confirmation that their actions have succeeded to maintain confidence and control. Feedback is vital for users to keep enjoying a seamless experience—any pause where they wonder what’s going on can break that. This is why designers design for feedback and micro-interactions—those valuable signatures of interaction design where, for example, a button changes color when a user hovers over it. From a password manager that shows immediate visual confirmation and a success message when a user saves credentials, to a triumphant vibration from a smartphone to notify a user of a successful action, feedback is fundamental to the user experience.

Great looks are no substitute for usability. A design can be beautifully useless and go nowhere. The aesthetic-usability effect shows that attractive designs can feel easier to use, but designers must balance this phenomenon with actual functionality. It can depend significantly on the brand or industry—for example, a meditation app might combine calming visuals with clear, accessible controls that don’t interfere with the peaceful experience.

When designers thoughtfully apply these cognitive science principles, they can create experiences that align with how humans naturally process information, make decisions, and learn new systems.

Cognitive science as a discipline has its most directly visible roots in the following areas.

In the 1940s, wartime aviation research revealed that poor control layouts and unclear labeling caused dangerous errors, a problem that led to “human factors” engineering—designing equipment to match human abilities. Psychologist Paul Fitts’s 1954 work quantified how quickly people can move to and select targets. His law influencing interface design rules is still in use today.

Psychologist George Miller’s 1956 paper “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two” suggested people could hold about seven items in working memory, but working memory specialist Nelson Cowan’s later work refined this to closer to four chunks in many cases. This finding strongly supports chunking content—such as remembering a phone number in two or three blocks of digits as opposed to the whole number as a string—and using staged disclosure.

By the 1980s and ’90s, cognitive psychology had underpinned the emerging field of human–computer interaction (HCI). Researchers developed structured models like GOMS (Goals, Operators, Methods, and Selection rules) and introduced the cognitive walkthrough, a step-by-step inspection method to predict how easily a new user could learn a new task.

The “Godfather of UX design,” Don Norman’s book The Design of Everyday Things (1988, revised 2013) translated these concepts into everyday design language—such as mental models, mappings, feedback, and constraints—and added the modern emphasis on signifiers for digital environments. Norman had noticed the need for improved usability on even simple designs such as doors which didn’t indicate whether a user should push or pull them to open.

Today, cognitive science principles shape everything from mobile app onboarding to the layout of complex dashboards, and designers who leverage them mindfully can ensure that the interfaces they create fit human mental processes. From that, they can prove a solid understanding of their user behavior and meet—and, ideally, exceed—their users’ needs.

Discover how to develop a true designer’s mindset from Don Norman, as he discusses what design should do and how costly bad design can get, in this video.

The following suggested process blends core cognitive principles, Don Norman’s design philosophy, and a practical evaluation method to help uncover learnability issues early in the UX design process.

Get right into user research to learn about your brand’s target users and:

Identify the most important tasks for a first-time or occasional user through a cognitive task analysis, to uncover hidden challenges and more.

Consider what they likely know at the start and their environment—such as their device type, distractions, and time pressures.

Apply mental models: match interface logic to what the user already understands.

For example, for a food delivery app, a first-time user’s main goal is to order a meal quickly—so, don’t overwhelm them with loyalty offers before they’ve even placed their first order.

Discover how to use task analysis to learn what’s important to users in the moments when they need to take actions, in this video with Frank Spillers: Service Designer, Founder and CEO of Experience Dynamics.

Now that you’re building up a clearer picture of the users and what they go through in their contexts, you can inform your design decisions better. One “tool” that’s especially helpful is personas—synthesized representations of real users—so you can keep your target users top of mind.

Discover how personas are more than helpful—to design without them falls short, in this video with William Hudson: User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd.

From your earliest design prototypes, consider how to help your product’s users help themselves:

Use the Hick–Hyman law and stage and group options to speed decisions and prevent analysis paralysis.

Apply Gestalt grouping using such laws as proximity and similarity, for example, and hierarchy to make scanning easy.

Reduce cognitive load: break tasks into manageable steps so users don’t feel they’re having to do “work” to use the digital product.

For example, consider an online tax form that shows only three income categories on the first page and then expands the chosen category into specific forms on the next page. This measured approach to what users see keeps them from becoming overwhelmed (which, for actions like calculating taxes, can feel daunting to start with).

Airbnb neatly applies proximity in a clear and user-friendly interface—elements lined up precisely with consistent spacing in a grid-like layout. They cluster elements that relate to the user's search, too, and their use of color and typography highlights important information and actions.

© Airbnb, Fair use

Apply Fitts’ law and make important targets large enough and positioned for easy access so users don’t have to reach far or look for elements.

Use affordances and signifiers to ensure interactive elements clearly look interactive and users are not left wondering. For example, “Buy Now” on a button shows in no uncertain terms what that large, well-placed button does.

Maintain logical mappings and place controls near the content they affect. For example, in a photo-editing app, crop controls appear directly around the image area and not in a distant toolbar.

Prototypes guide the way to better designs because you don’t invest too much in them—compared to finalized design solutions—and changes are far cheaper the earlier you catch flaws in usability testing. Therefore:

Keep early designs focused on essentials.

Use progressive disclosure to limit initial complexity.

Provide feedback loops: visible, immediate confirmation after actions.

For example, a budgeting tool prototype shows only the current month’s data by default, with a toggle to reveal historical charts—so test users won’t feel overwhelmed with information and can hopefully intuit their way around.

Find out how to get the most out of prototyping and pave the way to better designs with early discoveries from user testing, in this video with Alan Dix.

Speaking of “intuit,” cognitive walkthroughs provide an essential lens through which to evaluate a design, simulating a newcomer’s perspective so designers and design teams can spot learnability issues. To conduct a cognitive walkthrough:

Select a representative first-time task.

Write the ideal action sequence.

For each step, ask:

Will the user know they should take this step? (Mental model alignment)

Will they see the correct control? (Signifiers)

Will they connect that control to their goal? (Mapping and recognition)

Will they see progress afterward? (Feedback loop)

Flag any step where the answer is “no” or it’s uncertain.

Propose fixes and prioritize them.

For example, a fitness tracker’s setup flow walkthrough might reveal that the “Pair Device” button is buried in a settings menu instead of being visible on the welcome screen where users need it.

As much as cognitive walkthroughs can show you, the only way to learn if your design works—and how well it does—is to conduct usability testing with real users.

Test with your intended target audience.

Measure task success, errors, and time to complete.

Watch for aesthetic–usability effect bias—ensure users aren’t just forgiving a beautiful but flawed design.

Ask users to think aloud as they encounter and use the prototype, noting that their sighs and pauses can tell you much about frustration levels (which they might not verbalize for fear of offending you).

For example, five first-time users test a bank’s account-opening process; completion time drops from ten minutes (on the first design) to seven after designers have simplified the document upload step.

Design to appeal to users in ways that draw them to your product and brand. Balance Norman’s three levels of design:

Visceral: first impressions (style, tone).

Behavioral: ease and flow of interaction.

Reflective: how it feels afterward.

For example, users find a journaling app delightful because it uses calming colors and a clean font (visceral), offers frictionless daily entry logging (behavioral), and celebrates streaks with summaries (reflective).

Explore how to bring out the best feelings from users towards your design solutions, in this video with Alan Dix.

Accessible designs are non-negotiable, especially since they’re legal requirements in many jurisdictions. However, it’s good UX practice in any case because accessible features such as captions and high contrast help all users, such as (respectively) those in loud environments and those in bright sunlight. Some key accessible design practices include:

Reduce clutter to lower cognitive load for all users.

Use plain language, high contrast, and adjustable text sizes.

Arrange to test with assistive technologies—specialist agencies can handle this for you.

For example, a shopping site offers good accessibility via an optional “simplified view” with larger text, fewer elements per page, and no autoplay banners.

Get a greater grounding in how to make your digital products work well for users with disabilities as well as those without, in our video.

Given the nature and complexity of the human brain, the appliance of cognitive science carries some important considerations, and these are areas to watch for in particular:

Misusing the Hick-Hyman Law: Users may need essential options on show right away, so be careful what you decide to “hide” in the next screen or so. Long menus can still be quick if users find them well-organized and familiar.

Aesthetics masking flaws: Test functional clarity, not just emotional appeal—a uselessly beautiful design is just as bad as a beautifully useless design, so don’t let users down.

Neglecting signifiers: In digital contexts, make interactive elements unmistakably actionable. Even if it seems “redundant” or “users should know what this does,” microcopy on a button can make the difference between a quick conversion (and an enjoyable experience) and a hasty abandonment.

Walkthrough limits: Remember, walkthroughs help predict first-use problems but don’t replace live user testing—that’s testing with real users, not just members of a team “down the hallway.”

Accessibility: The dimensions of accessible design extend to many areas. Dense layouts can overwhelm; so, keep spacing generous—with negative space—and simplify what users encounter.

Ethics: Last, but certainly not least, use cognitive principles to assist, not manipulate. Good design involves helping users make decisions that benefit them via a digital solution—never trickery. In particular, beware of dark patterns—UI design patterns that “guide” users by automatically opting them in for subscriptions and the like through pre-checked boxes. Remember, good user experiences are ones where the user is in control.

Overall, cognitive science has provided designers and brands with a reliable way to align interfaces with how people think, act, and learn in the real world. Time-tested principles and understandings of “what works” help give valuable co-direction on how to create experiences that feel natural and intuitive.

Note the word “co-direction,” however. Indeed, a designer’s application of essentials such as conceptual models, mappings, and feedback ensures that interfaces can explain themselves. Still, designers must combine these principles with real-world testing and thoughtful iteration, and build products that work with the mind—not against it. When they succeed in delivering clarity, confidence, and lasting satisfaction from the very first interaction, it’s a healthy indicator that they’ve empathized with the user’s pain and designed well and truly for their brain.

Want to know more about personas and how to use them effectively? Personas and User Research: Design Products and Services People Need and Want will show you how to gather meaningful user insights, avoid bias, and build research-backed personas that help you design intuitive, relevant products. You will walk away with practical skills and a certificate that demonstrates your expertise in user research and persona creation.

Explore how to stay steps ahead of users by understanding how they think—enjoy our Master Class How to Design with the Mind in Mind with Jeff Johnson, Assistant Professor, Computer Science Department, University of San Francisco.

Find a treasure trove of practical, helpful insights in our article What Science Can Teach You about Designing Great Graphical User Interface Animations.

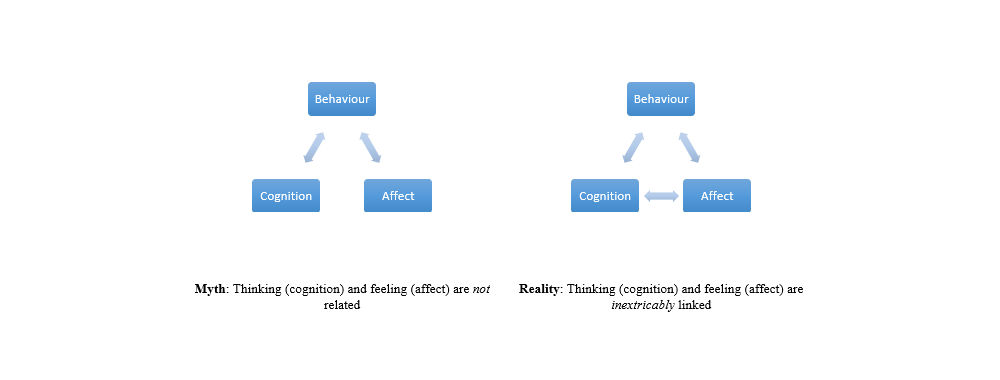

Explore important further aspects of cognitive scientific design in our article How Emotions Impact Cognition.

Get a greater grasp of how to design with cognitive science in mind using a helpful tool, in our article Cognitive Maps in UX.

Discover further insights in the Capital Numbers article The Psychology of UX: How Cognitive Science Influences Design.

UX (user experience) designers should understand attention, memory, perception, learning, and problem-solving. Attention determines which elements users notice, while memory (short-term, working, and long-term) influences recall of functions and navigation. Perception shapes how users interpret visuals, colors, and patterns. Learning theory explains how users adapt to interfaces, and problem-solving models reveal how they navigate tasks.

The Hick-Hyman law—sometimes called Hick's law—shows decision speed decreases as choices increase, and Fitts' law predicts how target size and distance affect usability. Cognitive load theory warns against overloading working memory.

Designers can apply these principles to create intuitive, efficient interfaces. For example, Google's search simplicity reduces cognitive load while speeding task completion.

Peer closer at perception to help create designs that make better sense to users and are more successful for it.

Cognitive load is the mental effort humans need to process information. In UX (user experience) design, excessive load slows task performance, increases error rates, and frustrates users. Working memory can only hold about 4±1 chunks of information at a time, according to modern cognitive science.

When interfaces demand too much processing—through cluttered layouts, excessive options, or unclear navigation—users feel overwhelmed and might abandon the website or app or misuse it. It's wise to minimize extraneous load to improve users' efficiency and satisfaction with a product and what they want to do with it. For example, Apple's iOS settings use clear categories and visual hierarchy to help users locate functions quickly.

By respecting cognitive limits, designers enable smoother workflows, faster learning, and higher engagement. Effective designs present only essential information at the right time, preventing overload and making sure users stay focused on their primary goals.

Delve deeper into cognitive load to understand how to design to minimize it.

Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts that can distort user decisions. UX designers should account for common ones like the anchoring bias (where the first information someone encounters heavily influences their judgment), confirmation bias (users seek data that supports their beliefs), and the primacy/recency effect (people remember the first and last items best).

Loss aversion makes users more sensitive to potential losses than equivalent gains, which affects how they take to pricing or feature adoption. The social proof bias drives people to follow others' actions, often seen in reviews or “bestseller” labels.

Recognizing these biases helps designers craft interfaces that guide decision-making ethically. Amazon, for instance, uses social proof with ratings while offering clear options to prevent manipulation.

Discover more about bias and learn how to design around it to ensure users encounter ethical, effective designs that benefit them.

To reduce cognitive overload, streamline interfaces and present only essential information at each step. Use progressive disclosure to reveal details as users need them so they do not feel overwhelmed upfront. Apply clear visual hierarchy so important elements stand out, and group related functions using the Gestalt principles of proximity and similarity.

Provide concise labels and familiar iconography to ease recognition. Limit options helpfully and ethically to help speed decision-making and reduce mental strain.

Clear feedback after actions reassures users and reduces uncertainty, helping them maintain focus. Ultimately, simplify interactions and align designs with natural cognitive limits for a more engaging, error-resistant, and accessible user experience.

Explore how to make the most effective use of visual hierarchy to make better digital solutions.

Faster, accurate decision-making for users depends on minimizing unnecessary complexity and leveraging user familiarity. Apply the Hick-Hyman law by reducing the number of visible options at any one time. Use strong visual hierarchy to direct attention to the most important actions. Provide clear, concise labels and avoid ambiguous terms.

Offer defaults that match common user goals and reduce the need for manual adjustments. Familiar UI (user interface) patterns, like standard navigation bars or “Buy Now” buttons, help users act quickly without relearning controls. Airline booking sites that highlight “cheapest” or “fastest” routes use this principle well to speed choices. Real-time feedback—such as visual confirmation after clicking—improves confidence. Overall, combine clarity, familiarity, and prioritization to empower users to decide faster while maintaining accuracy.

Discover how to pick UI design patterns to make effective designs that resonate with users.

Perception determines how users make sense of design elements. Visual cues like color, contrast, size, and spacing guide attention and suggest meaning. For example, red often signals errors or urgency, while blue suggests trust or stability. Gestalt principles—such as similarity, continuity, and closure—explain how users group elements and perceive patterns, even when they (the patterns) are incomplete.

Visual weight, created through size or boldness, signals importance. This is why designers follow design principles—poor use of these cues can mislead or confuse users. Meanwhile, mindful alignment improves clarity and flow. Understanding perception empowers designers to align aesthetics with function and ensure users interpret elements correctly and efficiently in better designs.

Get a greater grasp of design principles to leverage the most effective “rules” of design in better digital solutions.

Cognitive science helps predict user behavior by revealing how people process information, learn, and make decisions. Principles such as Fitts' law (or Fitts's law) can forecast how quickly users will click a button based on its size and distance. The Hick-Hyman law (or Hick's law) predicts how choice quantity impacts selection time.

Memory models indicate which interface elements users will remember after repeated exposure, which shapes navigation patterns. Recognition-over-recall strategies, such as labeled icons, reduce cognitive strain and make actions predictable.

Eye-tracking studies show consistent scan patterns (like the F-pattern for text-heavy pages), letting designers anticipate where users will look first. When designers apply these insights, they can help themselves create experiences that align with natural cognitive tendencies, increasing efficiency, satisfaction, and long-term adoption rates.

Find out how to design to align better with user behavior and user needs, in our article Hick's Law: Making the choice easier for users.

Cognitive science offers crucial guidance for designing inclusive experiences for neurodiverse users. Many conditions—such as ADHD and dyslexia—affect attention, sensory processing, and memory. Clear structure, consistent layouts, and minimal distractions help users focus. Customizable settings, like adjustable font size or contrast, cater to diverse user needs.

Provide predictable navigation and chunk information into smaller, digestible sections to reduce cognitive load. By baking inclusivity in from the start, designers can create products that respect different cognitive styles, enabling broader participation and improving usability for all audiences.

Enjoy our Master Class How to Design for Neurodiversity: Inclusive Content and UX with Katrin Suetterlin, Senior Professional Content Designer, SIXT SE.

Effective onboarding embodies cognitive principles to help users quickly grasp how to use a product. Progressive disclosure introduces features step-by-step, reducing cognitive overload. Contextual guidance—like tooltips or interactive walkthroughs—supports learning in the moment. Recognition-based instructions, such as icons with labels, lighten the memory burden. Spaced repetition, where key features reappear periodically, reinforces retention.

For example, Duolingo uses gamified onboarding with immediate feedback to encourage engagement while teaching core functions. Clear visual hierarchy highlights primary actions first, ensuring users can achieve small wins early. Apply these principles and you can ensure onboarding feels intuitive, lower abandonment risk, and boost users' confidence, setting them up for long-term success with the product.

Enjoy our Master Class How to Attract Users Through Great Onboarding Experiences with Wes Bush, Founder and CEO, Product-Led Institute and Author, Product-Led Growth.

Cognitive science informs cross-cultural design by exposing how perception, color meanings, and decision-making styles vary globally. For instance, color symbolism can vary from culture to culture—red, for example, may signify good luck in China but danger or caution in Western contexts. Reading direction affects layout—left-to-right cultures scan differently from right-to-left cultures. Hofstede's cultural dimensions, such as individualism versus collectivism, influence how people respond to personalization or group-oriented features.

Overall, use universal icons and avoid idioms that may not translate well. Global platforms like Airbnb adapt imagery, language, and payment flows to local expectations while maintaining a consistent core interface. Test with diverse user groups to ensure designs work across cultural contexts, improving usability, trust, and adoption in international markets.

Explore how to design with culture in mind, in this video with Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Copyright holder: Tommi Vainikainen _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Copyright holder: Maik Meid _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Norge_93.jpg

Copyright holder: Paju _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kaivokselan_kaivokset_kyltti.jpg

Copyright holder: Tiia Monto _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Turku_-_harbour_sign.jpg

Memory types—short-term, working, and long-term—shape how users interact with interfaces. Short-term memory stores small amounts of information briefly; overloading it with too many elements causes errors. Working memory manipulates this information during tasks, so designers should limit steps in complex processes. Long-term memory enables recognition of familiar icons, layouts, and workflows.

Recognition-based interfaces, such as visual menus, reduce the need for recall. Consistent design patterns strengthen long-term retention, while chunking content into smaller units aids processing. For example, web forms that break into sections are easier to complete accurately. Leverage memory principles and you can create smoother interactions, improve learning curves, and foster user confidence over repeated use.

Lift the lid on human memory to understand more about how to create designs that matter to users with grey matter.

Darejeh, A., Marcus, N., Mohammadi, G., & Sweller, J. (2024). A critical analysis of cognitive load measurement methods for evaluating the usability of different types of interfaces: Guidelines and framework for human–computer interaction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.11820.

This systematic review synthesizes evidence from experimental studies on cognitive load measurement in usability evaluation for a wide range of interfaces, including desktop software, mobile apps, and immersive environments like VR. The authors critically compare subjective, performance-based, and physiological measures, assessing their validity and suitability for different design contexts. They present a decision-making framework and practical guidelines to help UX professionals select measurement methods aligned with their interface type and research goals. By grounding usability testing in cognitive load theory, this work equips designers with scientifically validated tools to optimize user performance and reduce mental effort.

Kingsley, S. (2021). A cognitive science perspective for learning how to design meaningful user experiences and humancentered technology. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.07553.

This paper reviews literature across cognitive science, human–computer interaction (HCI), and natural-language processing (NLP) to explore how analogical reasoning (AR) can inform the design of communication tools, learning technologies, online communities, and digital platforms. It defines analogical reasoning and schema concepts, provides use-case examples from computing, and concludes with recommendations for further research into employing AR and schema methods in computing disciplines.

Norman, D. A. (2013). The Design of Everyday Things (Revised and expanded ed.). Basic Books.

Donald Norman's classic is a cornerstone of UX design, making cognitive science immediately relevant to everyday objects and digital products. By introducing the “gulf of execution” and “gulf of evaluation,” he illustrates how users think and act. Norman argues that design—not the user—is often at fault when things go wrong, and he provides clear principles such as visibility, feedback, and constraints. The revised edition keeps these timeless concepts fresh and applicable to modern technology, reinforcing the link between human cognition and intuitive design.

Johnson, J. (2020). Designing with the Mind in Mind: Simple Guide to Understanding User Interface Design Guidelines (3rd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann.

Jeff Johnson distills decades of cognitive psychology into a practical guide for UX designers. This third edition explains how users perceive visual elements, process information, and form mental models. With chapters on attention, memory, emotion, persuasion, and habit formation, it helps designers apply psychologically grounded principles rather than rote rules. The result is interfaces that are intuitive, persuasive, and cognitively aligned with human users.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Cognitive Science by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Cognitive Science with our course Personas and User Research: Design Products and Services People Need and Want .

In this course, you'll learn from one of the world's leading experts:

William Hudson: User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!