Design Thinking, Essential Problem Solving 101- It’s More Than Scientific

- 1k shares

- 9 years ago

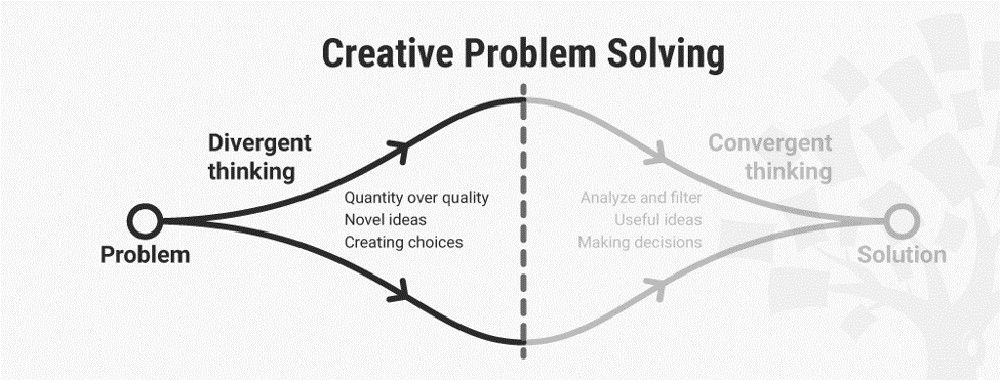

Divergent thinking is an ideation mode which designers use to widen their design space as they begin to search for potential solutions. They generate as many new ideas as they can using various methods (e.g., oxymorons) to explore possibilities, and then use convergent thinking to analyze these to isolate useful ideas.

“When you’re being creative, nothing is wrong.”

— John Cleese, Famous comedian and actor

Convergent and divergent thinking

The formula for creativity is structure plus diversity, and divergent thinking is how you stretch to explore a diverse range of possibilities for ideas that might lead to the best solution to your design problem. As a crucial component of the design thinking process, divergent thinking is valuable when there’s no tried-and-tested solution readily available or adaptable. To find all the angles to a problem, gain the best insights and be truly innovative, you’ll need to explore your design space exhaustively. Divergent thinking is horizontal thinking, and you typically do it early in the ideation stage of a project. A “less than” sign (<) is a handy way to symbolize divergent thinking – how vast arrays of ideas fan out laterally from one focal point: Design team members freely exercise their imaginations for the widest possible view of the problem and its relevant factors, and build on each other’s ideas. Divergent thinking is characterized by:

Quantity over quality – Generate ideas without fear of judgement (critically evaluating them comes later).

Novel ideas – Use disruptive and lateral thinking to break away from linear thinking and strive for original, unique ideas.

Creating choices – The freedom to explore the design space helps you maximize your options, not only regarding potential solutions but also about how you understand the problem itself.

Divergent thinking is the first half of your ideation journey. It’s vital to complement it with convergent thinking, which is when you think vertically and analyze your findings, get a far better understanding of the problem and filter your ideas as you work your way towards the best solution.

Here are some great ways to help navigate the uncharted oceans of idea possibilities:

Bad Ideas – You deliberately think up ideas that seem ridiculous, but which can show you why they’re bad and what might be good in them.

Oxymorons – You explore what happens when you negate or remove the most vital part of a product or concept to generate new ideas for that product/concept: e.g., a word processor without a cursor.

Random Metaphors – You pick something (an item, word, etc.) randomly and associate it with your project to find qualities they share, which you might then build into your design.

Brilliant Designer of Awful Things – When working to improve a problematic design, you look for the positive side effects of the problem and understand them fully. You can then ideate beyond merely fixing the design’s apparent faults.

Arbitrary Constraints – The search for design ideas can sometimes mean you get lost in the sea of what-ifs. By putting restrictions on your idea—e.g., “users must be able to use the interface while bicycling”—you push yourself to find ideas that conform to that constraint.

© Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

Take our Creativity course to get the most from divergent thinking, complete with templates.

Read one designer’s detailed step-by-step account of divergent thinking at work.

This UX Collective article insightfully presents an alternative approach involving divergent thinking.

Divergent and convergent thinking serve different purposes in UX design—but both are vital to finding the best ways forward with design ideas. Divergent thinking expands possibilities. It’s about generating a wide range of ideas—no matter how bold, strange, or unexpected, and sometimes the worse, the better, such as in the bad ideas or worst possible idea approach. You use divergent thinking during ideation to explore new directions and rethink problems from multiple angles—many of which are hard to access without being bold and even “ridiculous” in an approach.

Convergent thinking does the opposite—hence why it comes later. Designers and design teams use it to narrow down options by evaluating, organizing, and selecting the most promising and effective solutions. This phase helps designers and teams focus, test, and refine what works best for the user.

In practice, UX designers often move between the two. First, they diverge to explore freely—then they converge to make decisions based on evidence. The key is knowing when to switch modes: explore broadly, then hone sharply.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix discusses divergent and convergent thinking:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

To train yourself to think more divergently, practice generating lots of ideas—without judging them. Set a timer and aim for quantity over quality. Use exercises like Crazy 8s, mind mapping, or brainwriting—to name a few—to explore wild, impractical, or even downright ridiculous options. Often, the most unconventional ideas are the ones that spark something useful.

Ask open-ended questions like “What else could this be?” or “How might a child solve this?” These reframe problems and unlock creative pathways your brain usually filters out. That’s vital for climbing over assumptions that might block you otherwise. Try to limit your tools, too—sketch on paper or brainstorm with simple prompts. Constraints—paradoxically—boost creativity by forcing your mind to stretch.

Lastly, seek inspiration from outside UX—dive into music, nature, or science fiction. The more varied your inputs, the more surprising you might find your ideas are.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains some helpful methods for thinking divergently—to get as many fresh ideas as possible and from many angles of a problem:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

You have a wide range of ones to choose from—here are some of the best:

Wrong thinking: Deliberately try to solve a problem in the worst possible way with the bad ideas or worst possible idea approach. This flips assumptions and reveals blind spots. Surprisingly, some “bad” ideas turn into brilliant ones when tweaked.

Crazy 8s: Sketch eight ideas in eight minutes to force fast, free thinking. Don’t aim for polish or refinement—aim for variety. You can even repeat the round to push past your first instincts.

Brainwriting: Each person writes down ideas silently, then passes them along for others to build on. It removes groupthink and encourages deeper exploration.

SCAMPER (Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, Reverse): This reframes problems by remixing existing elements in creative ways.

Metaphor mapping: Compare your UX problem to something unrelated—like a restaurant menu or a subway map. Strange analogies shake up rigid thinking and can bring on powerful insights.

Forced pairing: Randomly combine two unrelated objects or features (e.g., “shopping cart + meditation”) and ask how they might intersect. It might sound chaotic—but chaos often leads to fresh insights.

These exercises work not because they’re trendy—but because they shift your thinking. They don’t guarantee magic, but they do open doors you wouldn’t normally walk through.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains some helpful methods for thinking divergently—to get as many fresh ideas as possible and from many angles of a problem:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

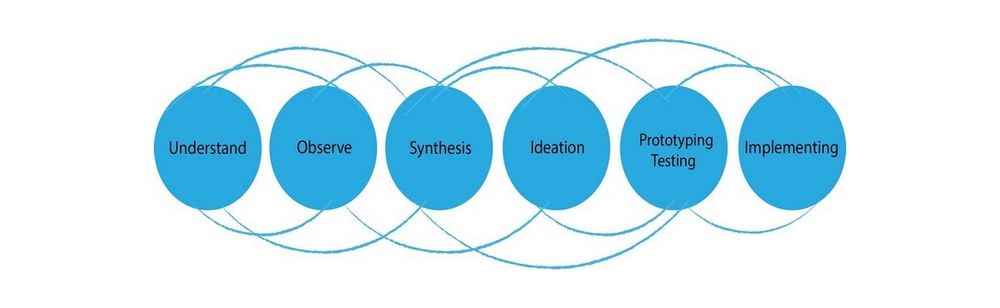

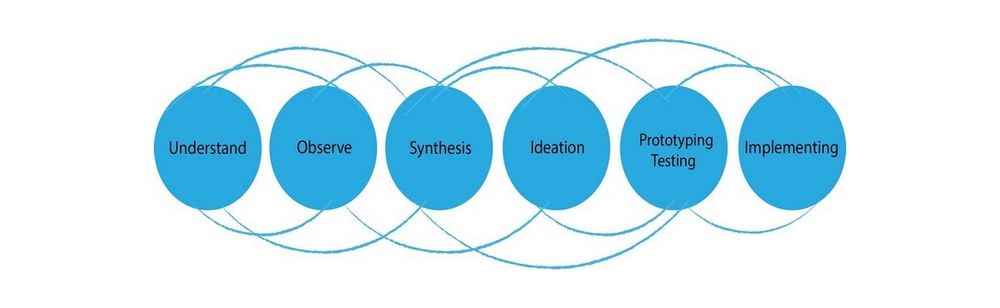

Divergent thinking plays a major role in the design thinking process—it fuels the creative exploration that leads to breakthrough solutions. During the ideation phase, teams deliberately generate as many ideas as possible without filtering or judging them. This open-ended mindset helps uncover unexpected paths, challenge assumptions, and reframe the problem in new ways. As such, it’s vital not only to design thinking but also to design itself.

Design thinking balances divergent and convergent thinking. First, you diverge to explore many ideas. Then you converge to evaluate, test, and refine the most promising ones. That back-and-forth is what makes design thinking so powerful—it avoids the trap of settling too quickly on obvious or safe answers.

Without divergent thinking, design thinking would be a linear process and far less effective—given what it can help teams achieve. With divergent thinking, teams stretch beyond the predictable and stay user-centered, inquisitive, and innovative.

Watch our video about design thinking:

Enjoy our Master Class Harness Your Creativity to Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author, and Creativity Expert.

To use divergent thinking without getting swamped, set boundaries that guide creativity without cutting it off. Start with a clear problem statement or “How Might We” question to anchor your brainstorming. Then, timebox the ideation phase—aim for 15 to 30 minutes of rapid idea generation so the session stays focused.

After you’ve explored widely, switch to clustering. Group similar ideas, spot patterns, and label themes. That will help you see connections and reduce overwhelm. Then, use simple voting methods—like dot voting or an impact/effort matrix—to narrow down the field.

Divergent thinking is most powerful when you pair it with a convergent mindset. Don’t rush to pick the “best” idea right away—instead, shortlist a few and prototype quickly to see what might work best. That way, creativity stays structured, not scattered.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains some helpful methods for thinking divergently—to get as many fresh ideas as possible and from many angles of a problem:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

Relying too much on divergent thinking can overwhelm you and your team and bog down your UX design process. While exploring ideas freely is essential, staying in a permanent brainstorm can stall progress and result in having too much to deal with. You risk generating endless possibilities without ever deciding, testing, or refining. The resulting sprawl leads to decision fatigue, scope creep, and delayed launches.

Too much divergence can confuse teams and clients, too. If your direction constantly shifts, it’s hard to build alignment or make practical progress. Ideas remain abstract instead of becoming useful, validated solutions—and when time is money, progress is important.

Effective UX design thrives on balance. Use divergent thinking to spark creativity, but pair it with convergent thinking to prioritize, simplify, and deliver. The goal isn’t to have more ideas—it’s to find the right ones and bring them to life.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix discusses divergent and convergent thinking:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

Cross-functional teams use divergent thinking to generate various creative ideas by drawing on their diverse expertise and perspectives. Each member brings a unique background—like design, development, or marketing—which sparks unexpected connections and out-of-the-box solutions. Working together in brainstorming sessions, they intentionally suspend judgment and explore multiple directions. This encourages everyone to contribute freely—no matter how wild, weird, or even “bad” the ideas seem.

This process fuels innovation. For example, a designer might suggest a bold UI idea that a developer refines into something technically feasible, while a marketer shapes it to appeal to users. The team doesn’t aim for one “right” answer initially—they aim for volume and variety. Later, they evaluate and narrow the options.

By combining divergent thinking with open collaboration, cross-functional teams break out of silos, challenge assumptions, and discover stronger, more user-centered solutions together.

Watch as UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains important points about cross-functional collaboration:

Enjoy our Master Class Harness Your Creativity to Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author, and Creativity Expert.

Frich, J., Nouwens, M., Halskov, K., & Dalsgaard, P. (2021). How digital tools impact convergent and divergent thinking in design ideation. Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–11.

This paper investigates how digital tools influence designers’ ability to engage in convergent and divergent thinking during the ideation phase of design. The authors conducted a mixed-method study involving professional designers using various tools in ideation sessions. They found that while digital tools facilitate documentation and sharing, they may inadvertently constrain creativity by promoting convergent thinking patterns. Conversely, analog tools tend to better support open-ended, divergent exploration. This work is significant in UX design because it challenges the assumption that digital tools inherently enhance creativity. Instead, it underscores the importance of tool selection in shaping creative processes and outcomes in design practice.

Wadinambiarachchi, S., Kelly, R. M., Pareek, S., Zhou, Q., & Velloso, E. (2024). The effects of generative AI on design fixation and divergent thinking. Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’24).

This 2024 CHI conference paper empirically investigates how generative AI tools influence design fixation and divergent thinking during visual ideation tasks. Conducting a between-participants study (N=60), the authors compare participants exposed to AI-generated images, conventional image searches, or no external prompts. They found that AI exposure significantly increased fixation on initial design ideas and reduced the quantity, variety, and originality of generated concepts. The paper suggests that the interaction method with AI—especially prompt crafting—strongly shapes ideation outcomes. Its findings challenge optimistic claims about AI-augmented creativity and offer valuable implications for designing AI tools that foster, rather than hinder, creative thinking in UX and visual design practices.

Sawyer, K. (2013). Zig Zag: The Surprising Path to Greater Creativity. Jossey-Bass.

In Zig Zag, Keith Sawyer, a psychologist and jazz pianist, presents an eight-step program designed to enhance creative potential. Drawing from extensive research into the habits of exceptional creators, Sawyer identifies key practices such as asking the right questions, learning continuously, and embracing play. The book offers over 100 practical techniques aimed at fostering creativity across various domains. By emphasizing that creativity is a process involving exploration and iteration, Sawyer demystifies the concept, making it accessible to a broad audience. This work is significant for its actionable insights and its challenge to the notion that creativity is an innate talent, positioning it instead as a skill that can be cultivated through deliberate practice.

Baer, J. (1993). Creativity and Divergent Thinking: A Task-Specific Approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

In this pivotal work, John Baer challenges the conventional belief in general-purpose creative-thinking skills, such as divergent thinking, applicable across all domains. Through a comprehensive review of existing research and presentation of new studies—including his APA’s 1992 Berlyne Prize-winning study—Baer demonstrates that creativity is task-specific rather than a universal skill. He proposes a multi-level theory that redefines divergent-thinking concepts into domain- and task-specific forms, bridging the gap between traditional divergent-thinking theories and modern modular conceptions of creativity. This book is significant for educators and researchers, offering insights into tailoring creativity training to specific tasks and domains, thereby enhancing its effectiveness.

UX designers use divergent thinking to solve problems by opening up a wide range of possible solutions before narrowing them down. Instead of jumping to the most obvious fix, designers use divergent thinking to explore many ideas—even strange or unexpected ones.

This kind of thinking encourages creativity, curiosity, and experimentation. It’s especially powerful during early stages like ideation or problem framing. Techniques like Crazy 8s, brainwriting, and “How Might We” questions help generate options without judgment.

When they start wide, designers avoid tunnel vision and uncover insights that wouldn’t surface through linear logic alone. Later, they can evaluate and refine the most promising ideas through user testing and iteration.

Divergent thinking isn’t about being random—it’s about thinking bigger to get a large “catch” or “haul” of ideas, so designers and design teams can proceed to analyze which are the best ideas to pursue.

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains some helpful methods for thinking divergently—to get as many fresh ideas as possible and from many angles of a problem:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Divergent Thinking by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Divergent Thinking with our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your experts for this course:

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Don Norman: Father of User Experience (UX) Design, author of the legendary book “The Design of Everyday Things,” and co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!