Early-Design Testing

- 495 shares

- 11 mths ago

Early-design testing is the practice where designers or researchers evaluate design concepts, prototypes, or user flows at the beginning of the UX (user experience) design process. UX designers use it to uncover usability issues, validate assumptions, and gather user feedback before committing to develop products more concretely.

Enter the zone of early-design testing and come away with insights that will put your product, service, or experience on the right track as soon as possible, in this video with William Hudson: User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd.

It might sound counterintuitive to test a proposed design so early in the UX design process—almost as if to suggest a design team hasn’t had time to build anything that’s truly testable—but it’s vital to do.

Designers typically test low-fidelity prototypes such as paper prototypes, wireframes, or clickable mockups with real users to determine how functional, clear, and usable the core parts and concepts of their design idea are. The goal is to gather actionable feedback before they plow significant time and resources into development.

Unlike later-stage usability testing, which often assesses polished interfaces or working software, this testing focuses on identifying potential friction points long before they can grow into true design faults. It helps answer key questions like:

Do users understand the layout?

Can they accomplish tasks intuitively?

Are design assumptions valid?

Since design teams can make—and quickly act on—assumptions from the moment they think about user behavior, user needs, and even a potential solution, they can run into the danger of getting carried away with unfounded ideas. They might assume users will see things their way and that the road ahead is all straight and smooth. If they proceed thinking that way, they can set themselves up for a shock later when usability tests expose a faulty high-fidelity prototype or even a flawed “finalized” solution.

One of the most compelling reasons to test early is cost. It costs far, far less to fix usability problems during the earlier stages of the design phase than to address such problems later, when teams have sunk time, effort, and money into higher-fidelity prototypes, or (worse) the product after launch, when users can rate—and berate—it.

The 1-10-100 rule mirrors this fact. A $1 problem that a team finds at the initial stage can cost $10 to fix if they don’t catch it until later, and it can skyrocket to cost $100 to address if they only discover the issue late in development or even post-release. This ratio set can scale painfully for brands that go too far with assumptions.

Early testing helps teams weed out such problems before they become cemented in code, and so they can remove them long before they can frustrate more users, hurt the product, and tarnish the brand’s reputation by “escaping” into the marketplace.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

As vital as user research is, designers often work from a set of assumptions—about what users need, how they behave, or which features will be most valuable. When they early-design test those assumptions in real-world conditions, they can challenge or confirm such notions about how users will respond to a design and its features. For instance, a team may assume users will recognize an icon’s meaning, but testing may show users find it confusing. If the team catches this early, they can easily course-correct.

Discover how user research helps lay the foundations on which to build successful design solutions, in this video with William Hudson.

Early testing builds a shared understanding of what users need and how they interact with a product. It grounds design conversations in hard evidence rather than fly them high into the cloudy realms of opinion. This is particularly valuable in cross-functional teams, where product managers, developers, and stakeholders may have differing views on what users need.

Discover how user needs fit into product design, in this video.

When teams validate design decisions early, they can slash the risk of launching a product that misses the mark. Early testing helps teams prioritize features users actually want. Teams can find out not only what doesn’t work but also insights about important features they had either not thought important or overlooked completely.

When designers and teams shift their focus to fixing faults and fine-tuning desired features, they can keep testing to work out the best way forward. This approach results in a final product that truly delights the target audience. From out of a scanty-looking wireframe can come insights from which designers can make essential adjustments to a proposed product before they set anything in “concrete” for users in the marketplace.

Get a clearer view of how wireframing helps set foundations on which to cement designs that can engage users in seamless experiences and deliver on what they want, and more, in this video.

Decide what you need to find out. Write clear, testable questions. For example:

Can users find the signup form from the homepage?

Do users understand the purpose of the dashboard?

Is the navigation intuitive for first-time users?

Match the fidelity of the prototype—and it should be a lower-fidelity one—to your goals. Use:

Paper sketches for basic flows or layout concepts.

Wireframes for navigation or content testing.

Clickable mockups for task-based scenarios.

Explore how to draw and cut your way to a paper prototype of a novel solution you can test early, in this video with William Hudson.

Find participants who reflect your intended user base so you can get the best insights from your target audience. Use recruitment tools, social media, or your (intended) customer base. Offer individuals incentives, if necessary, to encourage participation.

Outline tasks for users to perform during the test session. Keep instructions neutral and don’t use jargon or leading language. For example:

“Show me how you’d add a new contact.”

“Where would you click if you wanted to book a meeting?”

Conduct tests one-on-one, either in person or via remote tools. Use the think-aloud method, and resist the urge to correct or guide users. Remember, it should be early enough in the design process for you to make corrections relatively easily; that’s why you’re doing a test at this stage.

Take notes, capture quotes, and identify usability issues. Particularly watch what users do and their body language; frowns can tell you more than words. Speaking of words, some users might downplay their frustration so that they don’t offend you. In any case, look for patterns across sessions—do multiple users struggle with the same element?

Prioritize problems by severity and frequency; when users uncover significant issues, especially ones that arise often, your test will save you a great deal of time, effort, and money.

Explore how to get data working well for you, in this video with helpful tips about collecting data, with Ann Blandford: Professor of Human-Computer Interaction at University College London.

Now you’ve gathered some feedback, analyze it so you can make design changes based on feedback. If issues persist on the next test, consider alternative solutions. Continue testing until users can complete key tasks with ease and confidence—the hallmarks of an intuitive experience. Early-design testing helps pave the runway so a design solution can launch into clearer “skies.”

Reach into statistics, briefly, for a clear view of how to determine if the results of tests are significant, in this video with William Hudson.

Designers and teams have two helpful “allies” they can rely on to test specific areas: first-click testing and tree testing.

First-click testing is a method that evaluates where users click first when trying to complete a specific task on a UI (user interface). This initial click is crucial; research indicates that users who click correctly on their first attempt are far more likely to complete the task successfully.

Find out how this form of testing can help you spot vital points about where your design stands, and where you can take it to enjoy more success, in this video with William Hudson.

To run a first-click test, you present users with a static image or prototype of a webpage or app and give them a task, such as “Find the contact information.” So, they click—hopefully correctly—and you record and analyze their first click to see if your design, like a prototype, guides users intuitively.

This method is particularly effective in early stages, as teams can conduct it with low-fidelity prototypes. It could be to test how to “book an appointment” or “add a product to the cart”—you want to see what users do first and if they can do it without hesitation.

Create a Prototype or Static Image

Use an interactive prototype, wireframe, mockup, or even a sketch that you’ve rendered into a digital format. It should show the interface users need to begin a specific task. Sketches help bring form to ideas, while wireframes work as blueprints for a digital solution’s structure. Mock-ups showcase the visual appearance—how things will look on the proposed solution—while prototypes offer simulations of interaction and functionality at the higher end.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Write a Task Prompt

Clearly instruct the user on what they need to do—for example, “Where would you click to change your password?”

Ask for the First Click Only

Don’t let users complete the full flow. You want to see where they believe the task should begin.

Record and Analyze Results

Use heatmaps or click maps to visualize the click distribution and have the results for easy reference. Analyze how many users clicked the correct area and how far off incorrect clicks were.

Iterate and Re-test

If a significant number of users fail, it’s a sure sign you’ll need to adjust the layout or labels and test again to validate improvements.

Best Practices for First-Click Testing

Use neutral, task-focused prompts.

Test five to eight users per iteration.

Don’t give hints or feedback during the test (not even subtle sighs).

Visualize data using heatmaps to identify click patterns.

Prioritize revising elements that consistently mislead users.

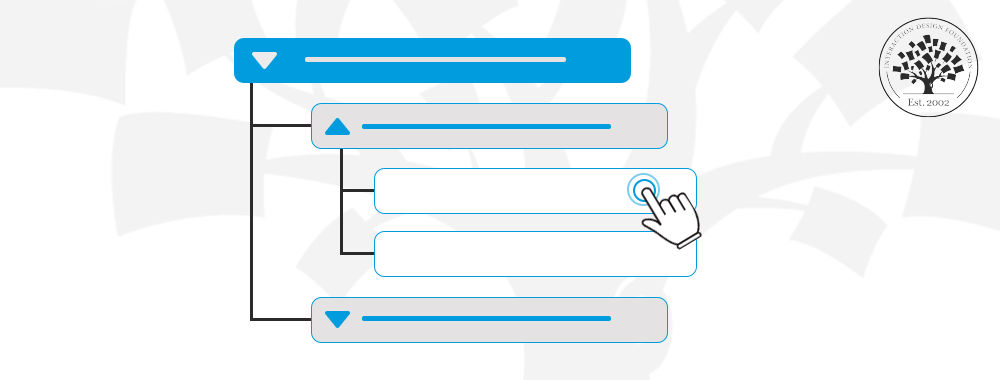

Tree testing assesses how clear and effective a website or application’s information architecture is to your test users. Where first-click testing revolves around visual design, tree testing strips away visual design elements; designers focus just on the site’s structure here.

Grab a hold of this helpful branch of testing to get a better view of your digital product’s information architecture—and learn what to tweak so your design can reach more successful heights—in this video with William Hudson.

To run a tree test, you give users tasks that require them to navigate through a simplified text version of the site’s hierarchy so they can find specific information. For example, you might ask them, “Where would you find information about shipping policies?” and then they would navigate through the text-based menu to locate it. You want to discover whether users can find information easily and if the site’s organization aligns with their expectations.

Build a Text-Only Site Structure

Use an online tool or sketch out your navigation paths; don’t include visual elements that might distract users from the structure.

Develop Realistic Tasks

Ask users to find content they would normally look for—for example, “Where would you look to track the delivery of your item?”

Run the Test Remotely or In-Person

Ask users to click through the hierarchy to find answers. Measure the success rate and time it takes them to do so.

Analyze Results

Look for patterns: Are users getting lost? Are they choosing incorrect categories? Use metrics like task success rate, directness, and time on task.

Refine and Re-test

Based on what you find out, restructure confusing categories, rename items, or reorganize paths. Then, re-test until you’re sure you’ve “hammered out” these kinks and have an information architecture (IA) that users understand well.

Investigate how a strong information architecture helps brands reach users better, in this video.

Best Practices for Tree Testing

Test at least 10 tasks with 5–15 users.

Use actual user terminology in your navigation.

Include distractor categories to mimic real-world complexity—for example, “Returns and Refunds” to distract from where to go for information about shipping policies.

Treat failed paths as learning opportunities—not user errors.

Combine findings with insights from open and closed card sorting if available.

Check out how card sorting can help get design ideas on track, in this video with Donna Spencer, Author, Speaker and Design Consultant.

Before you start, always decide what you want to learn. Your goal might be to validate a concept, test a navigation pattern, or explore user reactions to a new layout. When you have a clear objective, you can design the right test scenarios and analyze results more effectively.

Remember, “early” is in the name for a reason; don’t wait for polished visuals or complete flows. Early testing works best with rough concepts—paper sketches, wireframes, or clickable mockups. These lightweight prototypes are quick to create and easy to change based on user input.

Ideally, test with people who closely resemble your target audience. For example, if your product is for new parents, don’t test with college students. In early stages, even a handful of users—usually five to eight—can uncover critical usability issues.

This is where your research will help point the way. Better still, if you pinpoint your users and distill them into user personas—fictitious representations of your real target users—you can gear your future design decisions around more substantial focal points.

Prioritize personas as a powerful aid to fine-tune design solutions that can match and exceed the real-world expectations and desires of target users, and learn why design without them falls short, in this video with William Hudson.

Encourage users to verbalize their thoughts while they’re interacting with the prototype. This reveals confusion, assumptions, and expectations in real time—and it means users typically won’t have time to be politely dishonest out of fear of offending you. For example, a user might say, “I’m not sure what this button does”—a clear signal that you’ll need to include clearer labels or buttons.

Resist the urge to explain or help during the test. As much as a user may seem to “agonize” about how to achieve a goal, don’t give the game away; your job is to observe how they naturally interact with the design. Take detailed notes and record sessions, if possible, but focus on what users do, not just what they say.

Act on insights right away. Fix glaring issues, refine the prototype, and test again—still nice and early in the design process. Rapid iteration is the heart of early testing—it lets you improve designs before costly rework becomes necessary.

Overall, early-design testing empowers UX teams to create user-centered solutions from the very beginning. It’s like a safety-net that can save designers and teams from falling into an abyss from the earliest steps they take. “Abyss” is no exaggeration; a few steps in the wrong direction early on can lead to stumbling into massive problems if a team doesn’t course-correct before they release a flawed digital product.

Just a few precautions like early-design tests can prevent brands from losing out to competitors who did invest in early validation. It can also spare users from feeling overwhelmed by features they didn’t ask for or ignored by a design that fails to address their pain points. Indeed, also, it can save designers the pain of meeting with frustrated business stakeholders who might lose faith in UX design after their shiny new solution flops as a “dud” in the marketplace.

Whether you're launching a startup’s MVP (minimum viable product) or redesigning a legacy platform, early-design testing gives you the confidence to move forward with clarity. It helps you make sure you’re building the right product—before you get to building the product right.

Delve deep into our Data-Driven Design: Quantitative Research for UX course for a wealth of insights and tips into how to shape successful products from fascinating findings users provide.

Climb high and get the lowdown on how users visualize helpful design solutions in our article Tree Testing: A Complete Guide.

Discover additional helpful insights in the Marvel article How To Test UX Design Early On In Your Process.

Explore the MeasuringU article Nine Misconceptions About Statistics and Usability for further helpful information.

You can catch usability problems before they grow into expensive mistakes when you do early-design testing. It allows teams to gather real user feedback, refine ideas, and validate assumptions—before investing heavily in development.

Research shows that it can cost up to 100 times more to fix a problem in development than to fix it in the design phase. By testing early, teams reduce risk, save resources, and build products that better meet user needs. It also boosts creativity: designers explore multiple ideas freely, knowing they can quickly test and adjust.

Discover what problems assumptions can cause designers, and how to manage them properly.

Start testing your designs as early as possible—ideally right after sketching your first ideas, but make sure you have conducted solid initial user research, too. Early testing isn’t about putting polished screens in front of users. Even paper sketches or simple wireframes can reveal valuable user insights.

The earlier you test, the sooner you’ll spot usability issues, misunderstandings, or gaps in your thinking. This will save you and your team wasted effort and help you pivot quickly when you must. According to usability expert Jakob Nielsen, testing with just five users can uncover up to 85% of usability problems, so you don’t need a huge budget or complex setup to start.

Actionable tip: As soon as you can show something, test it. Use low-fidelity prototypes to get quick feedback. Don’t wait until the “design is ready”; “ready” here means early and frequent—the earlier you test, the more agile and user-focused your process becomes.

Get right down to it with low-fidelity prototypes to see how these early “versions” can turn into fine “tools” to test with.

Early-design testing helps answer key UX questions that guide better design decisions before you and your brand invest heavily in development. At this stage, you can explore questions like:

Can users understand the core concept of the product?

Do users know what to do next when they see the interface?

Are navigation paths intuitive and easy to follow?

Do users interpret icons, labels, and calls-to-action correctly?

Where do users get stuck or confused?

These questions uncover issues with information architecture, user flows, and interaction clarity—before anyone on your team writes any code. Did you know that if you test rough sketches or wireframes with just three to five users, it’s often enough to reveal 80% of major usability problems that may be there?

Actionable tip: Use think-aloud testing with clickable prototypes. Ask users to perform basic tasks and explain what they see, think, and expect. Their reactions will quickly show what’s working and what needs refinement.

Explore where effective navigation can take great designs and grateful users, and how it gets them there.

First-click testing and tree testing are particularly excellent methods for early-design testing—especially to evaluate navigation and interaction clarity. You can use both methods early to avoid costly navigation and labeling mistakes later.

First-click testing helps answer: “Where do users click first to complete a task?” This method identifies whether users understand how to begin an action, which is crucial since research shows that users who click the correct first element complete tasks successfully most of the time.

Tree testing evaluates your information architecture. It strips away visual design and tests whether users can find information in a pure text-based site map. This pinpoints problems in menu structure, labeling, or categorization—helpfully, before you even need to design a screen.

Get a firmer grasp of how users can behave in test situations from our article 4 Common Pitfalls in Usability Testing and How to Avoid Them to Get More Honest Feedback.

To test a user flow before you build a full prototype, use low-fidelity tools and focus on key tasks, not final visuals. Start with sketched screens or wireframes that outline the steps users would take. You don’t need interactivity—just enough context for users to follow the journey.

Then run a cognitive walkthrough or task-based usability test. Ask users to talk through what they expect each screen or step to do. This approach uncovers friction points in the flow before adding any design polish.

Use first-click testing to validate your navigation paths early: Can users identify the right starting point for a task? Combine that with simple paper or digital mockups to simulate progression between steps.

Overall, when you’re testing static screens in sequence with user flows, your goal is to test logic, not layout.

Discover helpful insights in our article Flow Design Processes - Focusing on the Users' Needs.

To run an early-design test session, focus on clarity, speed, and structure. Start by picking a simple prototype—paper sketches, wireframes, or clickable mockups. Then write a few realistic tasks users should try to complete, like “Find a product to buy” or “Schedule a meeting.”

To begin each session, set the context: Tell users what they’ll see is rough and that you’re testing the design, not them. Then ask them to think aloud as they navigate—this reveals confusion, hesitation, and false assumptions.

Use methods like first-click testing to check if users know where to begin a task, and observe them carefully to watch where they struggle. Don’t lead or explain—let users explore naturally.

Actionable tip: Record the session (with permission), take notes on critical moments, and run sessions with at least 3–5 users to spot patterns fast.

Harvest some helpful insights and tips about testing prototypes in our article Test Your Prototypes: How to Gather Feedback and Maximize Learning.

Test your designs early and often throughout the design phase—ideally after every major iteration. Frequent testing helps catch usability issues before they become expensive to fix and keeps your team aligned with real user needs.

A good rule is to test after sketching initial ideas, after wireframing key flows, and after each major update. You don’t need dozens of users—test with just 3 to 5 users per round and they can reveal up to 85% of usability problems.

Each test should answer a specific question, such as “Do users understand this flow?” or “Can they find key features?” Regular testing keeps your process lean, flexible, and user-centered.

Tip: Bake testing into your weekly sprint cycle. Treat it as a habit, not a one-off event.

Explore how design teams use design sprints to supercharge their output and keep team members focused on meaningful deliverables.

To prevent bias when testing early designs, focus on neutral observation and clear task framing. Bias often creeps in through suggestive language, body cues, or overexplaining the design—things that can slip by you without your realizing it.

To begin, write unbiased task instructions. Instead of saying, “Find the easiest way to book a flight,” say, “Show me how you’d book a flight.” Avoid words like “easy,” “correct,” or “best.”

Let users navigate on their own. Don’t lead them, hint, or correct them; even your body language or what you might think are subtle sighs can skew the results. Your job is to watch and listen. Encourage the users to think aloud, but don’t interpret their behavior in real time.

Stick to a consistent script, record sessions (as long as you get users’ permission to record them), and analyze patterns after—not during—the session.

Base your design decisions on firmer ground by understanding how bias can block accurate insights and weaken research findings.

To prioritize changes after early testing, focus on impact and effort. To begin, review all feedback and usability issues. Group them by theme—navigation, layout, copy clarity, etc.—then rate each issue by two factors:

Severity: Does it block users from completing a task? Does it confuse or frustrate them?

Frequency: Did multiple users experience the issue?

Use a simple impact–effort matrix: prioritize fixes that are high impact and low effort. Tackle critical blockers first—especially if they affect task completion or cause user drop-off. Don’t waste time perfecting things users didn’t struggle with.

Tip: Create a prioritization spreadsheet with columns for issue, user quote, severity, frequency, and suggested fix. This helps align your team and track changes clearly.

Explore further avenues of what matters most to users in feature prioritization.

The biggest mistakes designers make with early testing often come down to poor preparation, leading questions, and ignoring results. Here’s what to avoid:

Waiting too long to test: Many designers hold off until the design looks polished. However, testing early sketches or wireframes provides the biggest insights at the lowest cost.

Testing with the wrong users: Colleagues and friends aren’t stand-ins for your target audience. Test with real or representative users who reflect your product’s audience, not these “stunt doubles.”

Leading users: Saying things like “This should be easy” or explaining the interface biases the results and loosens your grip on where the product might end up. Let users explore naturally and observe their behavior without interference.

Skipping analysis: Running tests without logging patterns or prioritizing feedback leads to wasted insights—keep on top of things.

Explore more about how to keep on point from our article Four Common User Testing Mistakes.

Rivero, L., & Conte, T. (2013). Using an empirical study to evaluate the feasibility of a new usability inspection technique for paper-based prototypes of web applications. Journal of Software Engineering Research and Development, 1(2).

This study introduces the Web Design Usability Evaluation (Web DUE) technique, aimed at identifying usability issues in low-fidelity prototypes during the design phase. By conducting empirical evaluations, the authors demonstrate that Web DUE effectively uncovers usability problems earlier in the development process, allowing for timely corrections before coding begins. This approach is particularly beneficial for UX designers working with paper-based prototypes, as it offers a structured method to enhance usability without the need for fully developed digital interfaces.

Pettersson, I. (2018). Eliciting user experience information in early design phases. Chalmers University of Technology.

In this doctoral thesis, Pettersson presents the CARE approach—a methodology for eliciting rich user experience (UX) data during early design phases. Focusing on in-vehicle systems, the research addresses challenges in capturing user expectations and experiences when product representations are incomplete. The CARE approach emphasizes contextualization, anticipation, reflection, and enactment to gather nuanced UX insights. UX designers can apply this method to inform the design of novel systems, ensuring that user experiences are considered even before full prototypes are developed.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Early-Design Testing by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Early-Design Testing with our course Data-Driven Design: Quantitative Research for UX .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your expert for this course:

William Hudson: User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!