The MAYA Principle: Design for the Future, but Balance it with Your Users’ Present

- 1.1k shares

- 5 years ago

The MAYA principle, which industrial designer Raymond Loewy coined, stands for “Most Advanced Yet Acceptable.” It advises designers to introduce innovations that are progressive but still within the area of user comfort. UX (user experience) designers apply this principle to help create products that feel both fresh and familiar.

"The adult public's taste is not necessarily ready to accept the logical solutions to their requirements if the solution implies too vast a departure from what they have been conditioned into accepting as the norm."

— Raymond Loewy

The MAYA principle has been offering a guiding light for designers since Raymond Loewy (1893–1986) devised and began to apply it in the first half of the 20th century. The formula of MAYA’s success lies in how it encourages designers to find the right balance in what they create for the people who encounter and use products, which include anything from the smallest logos up to the largest items (such as jumbo jets and cruise ships)—and, indeed, digital products.

Loewy discovered a powerful truth about how humans “take to” new things: designs that push too far get rejected, but designs that play it safe are boring. He mastered the art of balancing what users already know with exciting new possibilities—so pushing at the frontiers of design and technology beyond users’ expectations, while keeping them on board. This approach to welcoming the future of design has proved successful because it respects the level of what people are prepared to embrace. There can be a fine line between “excited” and “shocked”; a design or product that seems to come too far from the future might enthrall many people—temporarily—before they shake their heads in bewilderment. Loewy put his finger on the public “pulse” and understood how to handle a timeless tension in design: the balance of novelty with familiarity.

To look back at the products Loewy designed and influenced in the 20th century is to capture snapshots of an exciting era filled with iconic logos and products, including redesigned soda bottles, refrigerators, and cars. To a 21st-century eye, the look of many such items may conjure terms like “retro” and “vintage.” However, therein lies the point: an automobile from 1950 inspired by the MAYA principle bridged the divide between future and present without shocking the public consciousness. Smart designers know to keep this practice going and keep one foot in the present while stepping into the future with the other.

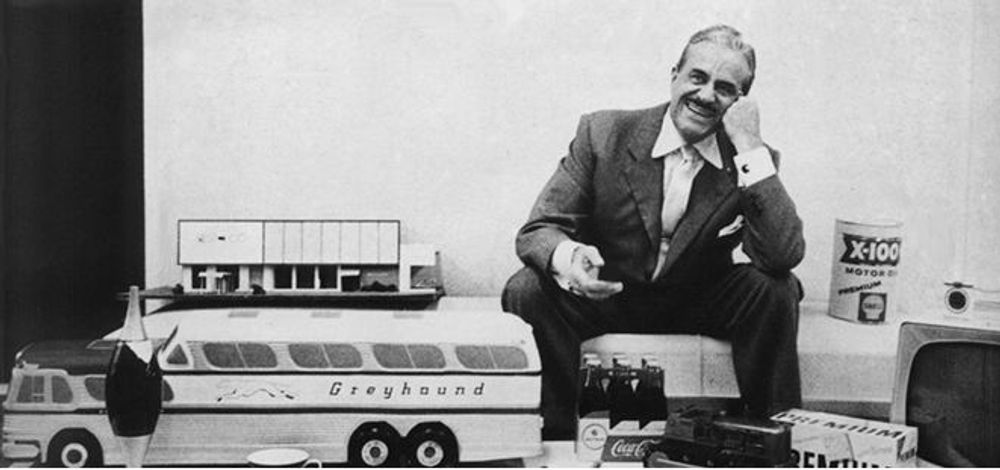

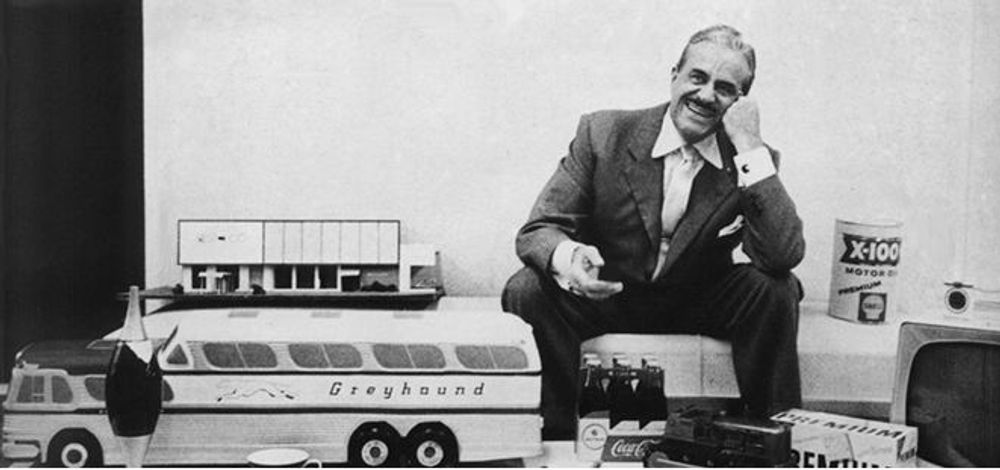

Raymond Loewy sits amid some of his iconic designs. Loewy is often dubbed the father of Industrial Design—and his “portfolio” includes the Air Force One logo, the Shell Oil logo, the US Postal Service logo, the Greyhound logo, and a variety of designs, many of which are still household names. Loewy coined MAYA after seeing that people resist overly unfamiliar innovations. Designers now use MAYA to introduce bold ideas gradually—whether through visuals, interactions, or structure—without alienating users.

© Raymond Loewy, All Rights Reserved

Human behavior reveals the science behind MAYA, and it’s a timeless concept. Psychologists call it the mere-exposure effect: people prefer what they recognize. Still, humans crave stimulation, too. This “move-stay” force creates a natural contradiction—one the MAYA principle resolves—and accounts for the point that while modern people may find “retro” items quaint, the reason few shockingly advanced outliers showed up in the marketplace was that designers typically knew better. For instance, even if 1950s designers could have created an outlandish-looking automobile which users could control just with their thought patterns, such advanced tech would have stayed behind closed doors—it would have been too much too soon.

Cognitive fluency explains another layer. The brain processes familiar things more easily—hence why people tend to find “faces,” “animals,” and other familiar shapes in natural formations such as clouds, for example—and fluency creates positive feelings. Even so, a little friction, in the form of innovation, also captures attention and encourages exploration. It’s one of the chief responsibilities of designers to walk this cognitive tightrope; the MAYA principle offers a framework to stay balanced.

Many aspects of the human condition show the MAYA principle or echo aspects of it. For example, a young child who is learning to count to ten won’t be ready to calculate the square root of 121 (11) until learning times tables later. This translates to any learner or user at any age—people need to be able to stand before they can walk, let alone run. The main point for the teacher—or designer—to consider is, when they want to help someone learn a new skill (or product), they must determine the person’s existing skill level first.

Learnability and comfort are essential to pushing boundaries and gaining new skills—and to decide how advanced and innovative a concept or design can be before the person who encounters it becomes confused. Soviet psychologist and founder of cultural-historical psychology, Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky (1896–1934) developed the zone of proximal development (ZPD) to describe the range of skills a child has while in the process of learning. The lower limit of the ZPD is the maximum skill level a child can attain by working independently, while the higher limit of the ZPD is the maximum skill level that the child can reach when a more capable instructor helps them.

Beautifully “classic,” but was this car with a Loewy touch, a Lincoln Continental, an instant “classic” on its release in 1946? Or more like something that rolled into dealerships as if back from the future to give exciting hints of things to come?

© Public domain

UX and UI (user interface) designers may handle the design of items that go more in the pockets and purses of users than their 1950s’ “counterparts” did in an era when consumer electronics were barely in their infancy. However, Loewy’s principle remains valid: teams who embrace MAYA can help themselves introduce forward-thinking solutions without overwhelming users.

Learnability goes a long way to reducing the chances of overwhelm. Vygotsky’s ZPD carries over to UX design in that it’s wise to gauge users’ current skill levels and the skills they can (easily) learn by themselves. For example, designers would accommodate this fact about users by making small changes in an existing product, or present users with a new product that has strong similarities to existing products or interaction patterns.

The MAYA balance applies to every UX layer—from visuals to interactions to underlying functionality. A product that follows the MAYA principle introduces fresh ideas within a familiar framework, encouraging trust and adoption. Design can be a risky realm if designers deliver too much “future” in the form of what they set before users. The “familiar” aspect must be there; if it’s not, its “foreign” nature may be too much for users. A successful design feels advanced—but not so alien that it becomes inaccessible and divorced from human relevance and relatability.

User experience hinges on two core human responses: curiosity and comfort. Curiosity drives interest in novel solutions, while comfort ensures ease of use and emotional safety. The MAYA principle supports both.

When UX professionals design “most advanced, yet acceptable” experiences, they can:

Encourage adoption of new technologies or workflows.

Reduce user anxiety around unfamiliar interfaces.

Increase retention by reinforcing intuitive behaviors.

Support business goals like innovation leadership without sacrificing usability.

It’s impossible to overstate how products that ignore this balance risk polarizing users. On the one hand, overly complex or futuristic designs may dazzle in demos but fail miserably in the marketplace—often far too exotic for users outside a niche of enthusiasts. Conversely, designs that cling to convention may feel outdated or fail to stand out—too nondescript or “stagnant” for most consumers to bother with. To consider this in a context where trust also extends to safety from cyberattacks, compromised privacy, and other problems online, designers have a prime opportunity to seize the moment and introduce a MAYA-tempered winning product.

Consider the evolution of electronic music players—and how touchscreens and smartphones have evolved away from the control wheels users once were “ready for.”

© Skyler Ewing, Pexels

To use MAYA effectively, assess where your product or idea lies on the spectrum between familiarity and innovation—and adjust accordingly and carefully.

To begin, identify mental models your audience already holds—the frameworks users use to predict how systems behave. For example, mobile app users expect tab navigation, swipes, and a back button. Regardless of where design may be heading—for example, in a more XR (extended reality), including AR (augmented reality) and VR (virtual reality), or even thought-controlled direction—respect these expected patterns unless there’s a compelling reason to deviate.

Discover powerful points about designing to match users’ mental models in this video with Guthrie Weinschenk: Behavioral Economist & COO, The Team W, Inc., specializing in behavioral economics, decision-making, and business strategy. He’s also the host of the Human Tech podcast, and author of I Love You, Now Read This Book.

Best Practices

Use established design patterns wherever they’re appropriate.

Study competitors to understand baseline user expectations.

Observe real users to identify their behaviors and pain points.

Explore how UI design patterns help designers fast-track their way to better digital solutions via familiar paths for users, in this video:

When you add advanced features or new interactions, make them discoverable and gradual. Don’t overwhelm users with a radically different system—even the smartest users likely won’t appreciate it, especially when they’re in busy situations. Instead, introduce novel elements inside known contexts.

Best Practices

Use progressive disclosure to reveal complexity over time.

Anchor new functionality with familiar visuals or metaphors.

Offer microcopy, tutorials, or onboarding cues to guide learning.

Explore how to leverage progressive disclosure by combining UI patterns in this video with Vitaly Friedman, Senior UX Consultant, European Parliament, and Creative Lead, Smashing Magazine:

Conduct usability testing to measure what users understand, accept, or reject. Start early and long before you even think to commit to any final design solution. Prototype innovative ideas and observe reactions. Are users intrigued or confused? Are they confident or hesitant? This feedback defines the limits of acceptability for your audience—it’s the users’ “toes in the water”; if the “temperature” isn’t right for them or there’s a powerful “current,” few will enter the experience.

Get insights into the power of prototyping from Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University:

Best Practices

Use A/B testing to compare novel and conventional designs.

Analyze abandonment points to see what’s causing cognitive overload.

Ask participants to “think aloud” to catch friction moments.

Discover how A/B tests can help you uncover essential insights about how users embrace design decisions, in this video with William Hudson: User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd.

What feels “advanced” today becomes normal tomorrow, and UX design must evolve with user expectations. Products like iPhones, Google Search, and Netflix slowly introduced major shifts by layering innovation over a stable core. For example, when Apple introduced gestures like pinch-to-zoom or swipe to unlock, it paired them with visual metaphors (like the “slide” animation). Each step built on existing interactions until gestures became second nature. The buttonless navigation users know—and expect—feels natural because of that gradual transition. This is why designers must monitor behavior and feedback; to time innovation correctly means standing on the shoulders of standards that will slowly sink into history.

Best Practices

Track usage metrics and session recordings over time.

Plan interface evolutions across product cycles.

Retire outdated patterns gradually to preserve users’ trust. This is especially important as many users will be slow to convert away from what they know and (at least, think they) love.

Google innovated in subtle ways—adding auto-complete, voice search, and predictive results without changing the core search bar. Users still enter text, but the underlying system has been advancing constantly and will continue to.

© Google, Fair use

While MAYA serves most design challenges, it isn’t universal. In some contexts—like emergency systems or highly specialized tools—efficiency may trump comfort, and the need to get something new on the scene becomes all-important. Sometimes, designers must disrupt expectations to break harmful habits or reframe behavior. The evolution of medieval armor serves as a reminder that design also responds to necessity—plate armor resists piercing and slashing better than chain mail. For a more serene example, the mobile defibrillator and mobile coronary care program—begun by the Pantridge-Geddes team of doctors in 1966 and incorporating a car-battery-powered device—needed to hit the ground running as a radical new concept. What started as a system in the hands of specialists has saved millions of lives since, and most people can use a defibrillator.

Still, even in these cases, it’s wise for brands to implement transition strategies and user education to soften the shift.

Designers who try to make design solutions appear futuristic can go too far. A sleek UI with unrecognizable icons or hidden controls may confuse rather than impress. So, be sure to strip down to essentials, validate early, and prioritize clarity over cleverness. If a brand needs to supply users with extensive instructions and a thick manual, it may not be able to save its product from obscurity in the marketplace. If a product needs to have extensive features that permit advanced functions—such as Microsoft Excel—a smart application of Heckel’s law, where users accept complexity if the effort is worth the reward, can help.

Designers who follow conventions too rigidly can limit innovation and create stale experiences—“by the book” won’t get a second look from users who may leave for more forward-thinking products. So, study where users show readiness for new ideas and offer optional beta features or early access programs.

A single usability test may not capture long-term adoption—especially as users sometimes resist at first, then grow to love new interactions. Combine short-term testing with long-term usage tracking; be patient but observant—some design features may be “slow boilers” and gradually become massive hits with users. Careful research and testing will help turn up trends and straighten bends that might otherwise block insights.

Get a greater grasp of why user research is so vital to help designers find out what works—and what needs work—from the people they create digital products for, in this video:

Use this checklist to help align with the MAYA principle:

Does the design feel familiar to the intended user?

What element introduces a sense of novelty or progress?

Does it introduce new features gradually and with support?

Do prototypes cause positive reactions in user testing?

Are advanced elements visually or functionally grounded in known patterns?

Can users achieve core goals without having to relearn everything?

Is our brand monitoring metrics post-launch to detect friction or drop-offs?

Spotify applies advanced AI to recommend music, but it packages that intelligence in familiar formats—playlists, album covers, and shuffle buttons. The innovation happens behind the scenes, keeping the user experience approachable.

© Spotify, Fair use

Overall, the MAYA principle reminds UX designers to lead users into the future with care. Technological advancements may be predictable to some degree. However, the “nature” of time is more like a curving corridor, and it’s hard to tell exactly what lies ahead—a fact mirrored in science-fiction movies that portrayed such luxuries as flying cars in 2019 (Blade Runner, 1982) or flying skateboards in 2015 (Back to the Future Part II, 1989). Note that such items will likely succeed if they evolve at just the right rate away from their ground-bound counterparts. In any case, innovation only thrives when people feel confident enough to use it.

Fortunately, design will keep moving in a healthy continuum—futurists will continue to thrive because humans naturally progress; nobody wants to be stuck in a state of decay. The “trick” is to lead users with little steps towards something exciting rather than a hard pull into angst-filled uncertainty. When designers balance the new and the known, they can create experiences that push boundaries without breaking trust—and leave a gentle trail of devices and design styles leading back to the “Grand Museum of Tech.” Designers can use MAYA as a trusty rule to keep users close—even as they guide them forward with brand-new products, new navigation models, or other design innovations. MAYA UX design isn’t a compromise between creativity and usability; it’s the craft of marrying both.

For a vast wealth of insights into how to craft products and experiences that users will take to, take our course Get Your Product Used: Adoption and Appropriation.

To expand into a wider realm of ideas from which you might enchant users with products they find “iconic,” enjoy our Master Class Harness Your Creativity to Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author and Creativity Expert.

Get an additional grasp in our article The MAYA Principle: Design for the Future, but Balance it with Your Users’ Present.

Explore more “MAYA” in the UX Collective article Most-advanced-yet-acceptable principle meets digital product innovation.

Find fascinating points in this UX Booth article, Deliver the Future, Gradually.

Designers use the MAYA principle—Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable—to create products that feel fresh but still familiar. It helps balance innovation with user comfort, so designs do not feel too strange or outdated.

In UX and product design, this means designers push boundaries just enough to spark interest without overwhelming users. A new app interface, for instance, might introduce gestures instead of buttons, but the designer does well to ensure it still resembles familiar layouts.

Research shows users prefer designs that are novel yet understandable. This keeps them engaged and improves usability—excited while still able to accommodate within their known experience.

Get valuable insights about the power of user research and what you can do with it, in this video:

Raymond Loewy—often dubbed the father of industrial design—came up with the MAYA principle: Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable. He believed successful designs blend innovation with familiarity, so people feel excited without feeling overwhelmed.

Loewy's work revolutionized 20th-century design and gave many now-iconic items their signature look. He shaped everything from Coca-Cola vending machines to the Shell logo and streamlined locomotives. He noticed that consumers didn't always embrace the newest, most cutting-edge designs. Instead, they gravitated toward products that felt new but still recognizable. This observation led him to develop the MAYA principle as a design strategy.

The MAYA principle helps ensure users feel comfortable with new features, layouts, or systems. When you apply MAYA and cheer “The future is here!” in a way that lets users get their minds around a hot new slice of modernity, you improve adoption and user satisfaction.

Grab an additional grasp of the MAYA principle in our article The MAYA Principle: Design for the Future, but Balance it with Your Users' Present.

The MAYA principle goes far beyond simplicity. While simplicity focuses on clarity and ease of use, MAYA—Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable—balances innovation with user comfort. A design might be simple but still feel unfamiliar or outdated; designers do best in this department when they apply MAYA to make sure it feels both fresh and relatable.

Simplicity removes friction, often by reducing elements or steps. Think of a clean app interface with just a few buttons. MAYA adds a strategic twist: it keeps enough familiarity to prevent confusion while introducing new, exciting features that feel intuitive. This creates emotional resonance and encourages adoption; users feel on board something that's “moving” ahead—but not whisking them away from their frame of reference.

Explore a fascinating angle of simplicity at work in design, in this video with Morgane Peng: Designer, speaker, mentor, and writer who serves as Director and Head of Design at Societe Generale CIB:

To apply the MAYA principle—Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable—to a new product, blend innovation with elements your users already recognize. Push the design forward, but not so far that it feels unfamiliar or confusing.

Start with solid user research. Understand what your audience already knows and expects. From there, you can identify where you can introduce improvements or new features. Use familiar UI patterns or visuals as a foundation and layer in innovation gradually. For example, if you're redesigning a calendar app, keep the grid layout users know, but introduce smarter scheduling tools or AI features that feel intuitive.

Testing will help prove what works and what needs work—so test early and often. Gauge reactions to the “newness” of your product. If users feel lost, dial it back. If they're bored, turn up the innovation factor.

Enjoy our Master Class How to Get Started with Usability Testing with Cory Lebson: Principal User Experience researcher with 20+ years experience and author of The UX Careers Handbook.

To know if a design is too far ahead or “much” for users, watch how they interact with it. If they hesitate, get confused, or abandon tasks, your design may have crossed the line of “acceptable” in the MAYA principle—Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable.

Use usability testing early; it will help save you headaches later—and wasted resources. Ask users to perform tasks without guidance; if they struggle to understand core functions or interfaces, that signals the design feels too foreign. Tools like heatmaps, task success rates, or time-on-task metrics can show friction, too. Even in surveys or interviews, users might describe a design as “cool but complicated”—a red flag. Actions speak louder than words, and users will tend to put politeness ahead of honesty, so watch what they do—closely.

Familiarity drives adoption—and innovative features only work when users can connect them to what they already know. So, keep “the future” within their frame of reference and pair bold changes with recognizable patterns.

Get right into usability testing to see how to make the best of early wins, whatever you learn from users about your design.

Avoid using the MAYA principle—Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable—when your users need clarity and consistency more than innovation. In high-stakes or utility-first contexts like medical devices, legal software, or air traffic control systems, even small changes can confuse or slow users.

You should set MAYA aside, too, during onboarding or for audiences who have low digital literacy. These users benefit more from straightforward, familiar designs than advanced features or experimental layouts, even ones blended with what might be familiar to users. In these cases, prioritize clarity and usability over novelty—confusion can cost more than staleness.

Another red flag is when innovation adds complexity without value. If a “fresh” idea disrupts user flow or increases cognitive load, it's better to stick with familiar, proven patterns and leave the grand idea on the backburner.

Explore the intriguing realm governed by Heckel's law, where users will tolerate complexity as long as the product they're engaging with gives them serious value.

The MAYA principle—Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable—shows up in mobile app design by blending cutting-edge features with familiar patterns users trust—mobile UI design patterns. It ensures apps feel fresh and exciting and new but easy to navigate.

For example, many fintech apps use biometrics and smart budgeting tools—advanced features. However, they still rely on common tab layouts, recognizable icons, and familiar gestures like swiping. Designers apply MAYA when they anchor new features in known conventions. A health app might debut an AI coach, but it keeps standard calendar views and activity rings so users can keep their “feet on the ground.” This helps users feel in control while exploring new tools—trust is all-important.

Vital advice: test early; test often. If users hesitate or drop off, the design might feel too unfamiliar; time for refinement or a rethink.

Make the most of mobile UX design, starting with a firm foundation in what this important area covers.

User personas—fictitious representations of real users—help apply the MAYA principle by showing what users already know and what they're ready to explore. These design tools can guide you to find the sweet spot between familiarity and innovation.

A well-crafted persona reveals users' goals, tech comfort level, and mental models. For instance, a persona of a tech-savvy early adopter might welcome cutting-edge gestures or AI-driven features. In contrast, a persona for older users might prefer straightforward, familiar layouts. These insights prevent you from over-innovating or over-simplifying.

Personas also highlight user expectations. When you align your design with these expectations, users feel more confident—even when they're facing something new—and that's the heart of MAYA: exciting enough, yet comfortable and trustable so users can climb on board without worrying about an “unknown destination.”

The powerful edge personas can give your design efforts is impossible to overstate. Want to know more about personas and how to use them effectively? Personas and User Research: Design Products and Services People Need and Want will show you how to gather meaningful user insights, avoid bias, and build research-backed personas that help you design intuitive, relevant products. You'll walk away with practical skills and a certificate that demonstrates your expertise in user research and persona creation.

The biggest mistakes include pushing too far into “advanced” or playing it too safe with “acceptable.” Both extremes defeat the goal of balancing innovation with user familiarity. One analogy might be a futuristic amusement park ride that promises the thrills of a lifetime, protected with force field tech. If users don't see safety harnesses on the seats, well-oiled hydraulic pistons, and sturdy support structures, the number of people who actually climb on board and trust the “force field” that keeps them safe will be extremely small.

Ignoring user research is another pitfall. Without understanding your audience's baseline knowledge, you risk introducing features that confuse rather than excite. Another common error: overloading users with too much novelty too quickly. Even innovative elements need familiar anchors—like standard icons, layouts, or interaction patterns—people won't be prepared for something new until they feel they're ready.

Another risk is: don't confuse simplicity with familiarity. A minimalist UI can still feel foreign if it doesn't have expected cues—enough hints to ground users in some familiar territory they can proceed from. Last, but not least, testing too late in the design process can hide how real users respond to your ideas.

To discover many essential insights and tips, enjoy our Master Class User Research for Everyone: Practical Strategies for Every Team with Alex McMahon, Design Lead.

When a design feels too futuristic, iterate using the MAYA principle—Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable—by anchoring innovation in familiar elements. Don't scrap bold ideas; instead, wrap them in recognizable structures.

First, find out what confuses users. Use usability tests to spot where they hesitate or drop off. Then, add familiar UI patterns, icons, or workflows around the advanced feature. For example, if a voice-controlled app feels too alien, offer visual prompts or fallback buttons. Gradually phase out these aids as users build up their confidence.

Moreover, offer onboarding cues or tooltips. These help bridge the gap between novelty and user understanding. Small changes—like renaming actions to match known behaviors—can make big differences in acceptance.

See how UI design patterns establish much-needed familiarity with users, in this video:

Hekkert, P., Snelders, D., & van Wieringen, P. C. W. (2003). Most advanced, yet acceptable: Typicality and novelty as joint predictors of aesthetic preference in industrial design. British Journal of Psychology, 94(1), 111–124.

This seminal article empirically investigates the interplay between typicality (familiarity) and novelty in shaping aesthetic preferences for industrial products. Through three studies involving consumer items like sanders, telephones, and teakettles, the authors demonstrate that both typicality and novelty independently and equally contribute to aesthetic appeal, but their effects can suppress each other. Notably, the research reveals that individuals prefer designs that strike an optimal balance between being familiar and innovative, aligning with the MAYA (Most Advanced Yet Acceptable) principle. The study's rigorous methodology and insightful findings have significantly influenced design psychology, offering valuable guidance for designers aiming to create products that resonate aesthetically with consumers.

Akiike, A., Katsumata, S., Yoshioka-Kobayashi, T., & Baumann, C. (2025). How “smart” should smart products look? Exploring boundary conditions of the Most-Advanced-Yet-Acceptable (MAYA) principle. Journal of Business Research, 189, Article 115108.

This study investigates the application of the MAYA (Most Advanced Yet Acceptable) principle in the design of smart products, such as smart speakers and smartwatches. The authors examine how the balance between typicality (familiarity) and novelty influences consumer preferences and acceptance of smart product designs. Their findings suggest that while innovative features are attractive, excessive deviation from familiar design elements can hinder user acceptance. The research provides valuable insights for designers and marketers aiming to optimize the aesthetic appeal and market success of smart products by carefully balancing innovation with user expectations.

Loewy, R. (1951). Never Leave Well Enough Alone. Simon & Schuster.

In this seminal autobiography, Raymond Loewy, often hailed as the father of industrial design, introduces the MAYA principle. He illustrates how designs that are too futuristic can alienate users, while those too familiar may fail to excite. Through anecdotes of his work on iconic designs like the Coca-Cola bottle and Air Force One, Loewy emphasizes the importance of introducing innovation that aligns with public readiness. This book is foundational for understanding the balance between innovation and user acceptance in design.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on The MAYA Principle by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Maya Principle with our course Get Your Product Used: Adoption and Appropriation .

Make yourself invaluable with powerful design skills that directly increase adoption, drive business growth, and fast-track your career. Learn how to strategically engage early adopters and achieve critical mass for successful product launches. This course gives you timeless, human-centered skills because understanding people, guiding behavior, and creating lasting value is essential across roles and industries. Make a meaningful impact in your career and in your company as you open up new markets and expand your influence in your current ones. These skills future-proof your career because understanding human behavior and social dynamics always surpass what AI can achieve.

Gain confidence and credibility with bite-sized lessons and practical exercises you can immediately apply at work. Master the Path of Use to understand what drives usage and captivates people. You'll use the economics of design, network effects, and social systems to drive product adoption in any industry. Analyze real-world product launch successes and failures, and learn from others' mistakes so you can avoid costly trial and error. This course will give you the hands-on design skills you need to launch products with greater confidence and success.

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your expert for this course:

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!