5 Common Low-Fidelity Prototypes and Their Best Practices

- 1.3k shares

- 2 mths ago

Wizard of Oz (WoZ) prototypes are UX (user experience) research set-ups where users interact with a system they believe is autonomous, but a human secretly operates it. Teams save time or technical effort when they test concepts this way, especially when simulating intelligent behavior like natural language processing, machine learning, or complex decision-making.

Explore the power of prototyping in this video, which addresses the Wizard of Oz approach to help guide better digital products:

The name of this popular UX approach comes from L. Frank Baum’s classic novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, where the “great and powerful” wizard that the protagonists journey to see turns out to be just a man pulling levers behind a curtain. The method itself dates to 1973 when it was used to test an automated airport computer-terminal travel assistant. It was first referred to as “Wizard of Oz” in a 1983 research paper for natural-language interfaces.

In the same spirit as Baum’s story, WoZ prototypes let teams stay flexible and validate high-tech ideas before investing in a sleek, finished product. More specifically, when design team members take a Wizard of Oz prototyping route, they can:

Savings in time and effort—and, indeed, money—form the primary benefit of WoZ prototyping; it’s vital to test ideas before committing to build the actual technology, anyway. For example, if a design team wants to explore a potential voice assistant feature, they can simulate responses manually rather than code natural language processing up front.

Since the interface behaves realistically thanks to the human who poses as it, users can engage with it as if it were real. The “magic” of a “wizard” means UX designers and researchers can observe authentic reactions and uncover usability issues, expectations, and mental models. From there, they can gain insights that might otherwise stay hidden—like if they used static mockups or scripted user testing.

Discover powerful points about designing to match users’ mental models in this video with Guthrie Weinschenk: Behavioral Economist & COO, The Team W, Inc. He’s also the host of the Human Tech podcast, and author of I Love You, Now Read This Book.

Before teams invest in features like AI-driven chatbots or automated scheduling tools, a WoZ prototype offers the freedom to test, learn, and refine ideas quickly. Team members can explore if users find it useful and intuitive. The worst-case scenario is “safe”—if the idea fails, they’ll have lost minimal resources; however, if it succeeds, they’ll have real-world evidence to support full development.

Explore the vast possibilities of prototyping in this video with Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University:

Wizard of Oz prototyping works best when design teams want to:

Test systems that simulate intelligent behavior, such as chatbots, virtual assistants, and recommendation engines.

Explore how users interact with new or unfamiliar concepts.

Avoid sinking resources into designs where the technical implementation is expensive or time-consuming.

Gather user expectations before they design actual functionality—a vital practice in user research.

Iterate on key interaction flows before they commit development resources.

WoZ prototyping can prove especially valuable in early-stage concept testing or when a team needs to develop an MVP (Minimum Viable Product). Another significant benefit is how teams can adapt their WoZ approach according to their needs. For instance, they can use cruder WoZ prototypes earlier on and more sophisticated ones later in the UX design process.

Discover how an MVP can help your brand reach its target audience earlier, as Frank Spillers: Service Designer, Founder and CEO of Experience Dynamics discusses:

Adaptability is a keyword in this design approach. The level of fidelity—or sophistication—a design team chooses can depend on the stage of their design process, available resources, and research goals. One thing that stays constant is how an operator posing as the “wizard” creates the illusion of system interactivity with the real users who test it.

The fidelity level refers to how closely the prototype simulates the final product in terms of visual design, interactivity, and system behavior:

They’re rough, early-stage simulations that often rely on paper interfaces, static mockups, or simple clickable wireframes. The interface might not respond in real time, and the wizard manually updates screens or responds through off-screen prompts. Low-fidelity WoZ prototyping is best when teams want to:

Explore concepts and ideate early.

Understand user expectations and general flow.

Do low-risk testing with minimal investment.

For example, a designer might make a paper interface for a voice assistant where the user speaks a command and the wizard displays the next “screen” manually.

The advantages of low-fidelity, or lo-fi WoZ prototypes are that they’re quick to build and revise, cost little to make, and encourage creative exploration. The limitations are that they may break immersion if users expect a more responsive or polished experience and that it’s harder to simulate complex interactions believably.

Discover how paper prototyping can help establish firm steps towards new solutions, as William Hudson, User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd, explains:

These prototypes use more refined digital interfaces with interactive elements, but the system’s intelligence still comes under the “wizard’s” control. The visual design may still be basic, but the interactivity feels more fluid and realistic. Mid-fi WoZ prototyping is best when design teams want to:

Test specific flows or interactions with a semi-realistic experience.

Simulate system feedback without backend development.

Observe detailed user behaviors and reactions.

For example, a team may have a chatbot interface where a wizard types responses behind the scenes.

The advantages of mid-fi prototypes are that they balance realism and flexibility, maintain user immersion better (than lo-fi), and are effective for usability testing. The limitations are that they take more setup and coordination and that wizards must be more skilled and attentive to maintain the illusion.

These near-production-quality interfaces look and feel more like the final product—hi-fi prototypes may include animations, branding, and polished UI components. The wizard still controls the underlying logic, but the front-end may be indistinguishable from a real system. Teams typically use hi-fi WoZ prototyping to:

Test user trust, emotional reactions, or high-stakes scenarios.

Gather fine-grained insights on interaction timing, feedback, and flow.

Do demonstrations for investors or stakeholders.

For example, a design team may test a virtual assistant prototype with real-time voice synthesis controlled by a wizard.

The advantages of hi-fi prototypes are that they’re highly immersive and believable and ideal for validating design polish and emotional response. The limitations are that they’re time-consuming and resource-heavy to build, and hard to adapt quickly during sessions.

The fidelity level depends on your goals; here’s a general rule:

For idea generation or early exploration, use low fidelity.

For flow validation or behavioral testing, pick mid fidelity.

For trust-building or final-stage simulation, go for high fidelity.

You’ll want to weave several key components to build a Wizard of Oz prototype—they’ll remain consistent across fidelity levels, but their execution changes depending on how realistic and complex your simulation must be.

The WoZ UI (user interface) is what users see and interact with. Its fidelity level directly influences the user’s perception of the system’s realism.

Low Fidelity

The interface might comprise hand-drawn screens, printed mockups, or basic wireframes—it could be a paper prototype or a simple slideshow. For interaction, participants might point or speak rather than tap or type.

Mid Fidelity

WoZ interfaces at this level usually include clickable wireframes or digital mockups built with design tools. Visuals are functional but not polished. The interface responds realistically to user actions, as the wizard triggers the correct screens or content behind the scenes.

High Fidelity

These interfaces closely resemble the final product and include branding, animations, and polished visuals—with users interacting via voice, touch, or gesture, and transitions appear seamless. The wizard still controls system behavior, but the visual and interactive layers feel complete; therein lies the “magic.”

The wizard simulates the intelligent behavior of the system, and their role remains hidden from users to preserve the illusion of automation.

Low Fidelity

The wizard manually adjusts paper or simple screens. The response time may be slower or more obviously human, but that’s acceptable at this stage—the focus is more on getting directional feedback.

Mid Fidelity

The wizard operates from behind a partition or in a separate room, and triggers responses through a dashboard or messaging app. Timing becomes more important—and delays should match what a real system might exhibit.

High Fidelity

The wizard must be in full “role-playing mode” here, and respond with near-perfect timing, using real-time inputs like synthesized voice, dynamic screen updates, or typed chatbot responses. The illusion of automation must hold for the “magic” to work, and the wizard may need a custom control interface to keep pace.

The script plays a vital role, too, as it helps the wizard stay consistent and efficient. It outlines how to respond to user inputs.

Low Fidelity

The script is often loose or structured around a few (anticipated) user actions. As users can see it’s not a real system, rigid consistency is less important than at higher fidelity. This flexibility is useful for teams to explore unexpected behaviors and gain vital insights they might otherwise miss.

For example, a team wants to test a smart assistant to help users find a restaurant, and so has a loose, flexible script, based on a few user intents.

Example Script:

If the user says, “Find me a place to eat,” show a printed menu of restaurants.

If they specify cuisine, such as “Italian,” flip to a paper screen showing Italian options.

If they ask something unexpected, say, “This is just a basic version—we’re focusing on restaurants today.”

Mid Fidelity

The script includes a wider range of expected inputs and matching outputs, and it accounts for common variations in user behavior. Wizards follow this more tightly to simulate realistic system behavior.

For example, a team wants to test a chatbot interface for booking flights, and so has a moderately detailed script that covers primary and secondary paths.

Example Script:

User: “I want to book a flight to New York.”

Wizard: (types) “Sure, what date would you like to travel?”

User: “Next Friday.”

Wizard: “Got it. Morning or evening flight?”

User: “Evening.”

Wizard: “Here are a few options for evening flights to New York next Friday.” (Displays mock options)

The purpose of this script is to test dialogue flow, understand phrasing patterns, and evaluate the logic of follow-up questions. It includes variations like the user changing the date, asking for baggage info, or requesting flexible travel times—issues an empathetic design team should have in mind, anyway.

Empathy for users goes a long way to staying ahead of their expectations and delighting them in design, as this video shows:

High Fidelity

The script is detailed, branching, and often has decision trees or real-time prompts to support it. It must cover edge cases and unexpected actions, since users assume the system is fully functional; consistency is crucial to maintain.

For example, a team wants to try out a voice-activated healthcare assistant for medication reminders—their script is highly detailed with decision trees, fallback strategies, and emotional tone guidance.

Example Script:

User: “Remind me to take my heart medicine.”

Wizard (using voice synthesis): “I’ve set a daily reminder at 8 AM for your heart medication. Would you like me to add a backup reminder?”

If user says, “Yes”:

“I’ll also remind you at 8:15 AM just in case. Anything else I can help with?”

If user says, “Actually, I don’t take it every day”:

“No problem. What days should I remind you?”

Unexpected user behavior: If they ask, “What are the side effects of this medication?”

Wizard follows protocol: “I’m not able to provide medical advice, but I can remind you to discuss that with your doctor. Would you like to add a note to your next appointment?”

The purpose here is to simulate real-time voice interaction with nuance, timing, and safety boundaries. So, the script must handle varied phrasing, tone, and health-sensitive topics with care.

The tasks or scenarios guide the user’s interaction with the system and ensure the session stays focused.

Low Fidelity

Simplicity is key; tasks are open-ended or exploratory—where you might ask, “Try using this to schedule a meeting,” and observe how users naturally engage.

Mid Fidelity

Tasks are specific but still allow for natural variation in behavior. They might include scripted goals like, “Ask the assistant to cancel your dinner reservation.”

High Fidelity:

Scenarios are often complex and involve multiple steps or emotional nuances. You might simulate high-stakes use cases—like managing finances or making health decisions—requiring the prototype to handle follow-up questions, clarification, or mistakes.

Where and how the session runs can make or break the illusion of a real system; remember the behind-the-scenes factor as fidelity levels increase.

Users and wizards are separate, so the user believes the system is partially functional. You might use screen sharing or a quiet observation room.

A fully immersive environment is essential for high-fidelity WoZ prototyping—the user should have no hint there’s a human intermediary; so, use one-way mirrors, hidden rooms, or audio booths. Sound quality, device responsiveness, and ambient cues must align with the illusion.

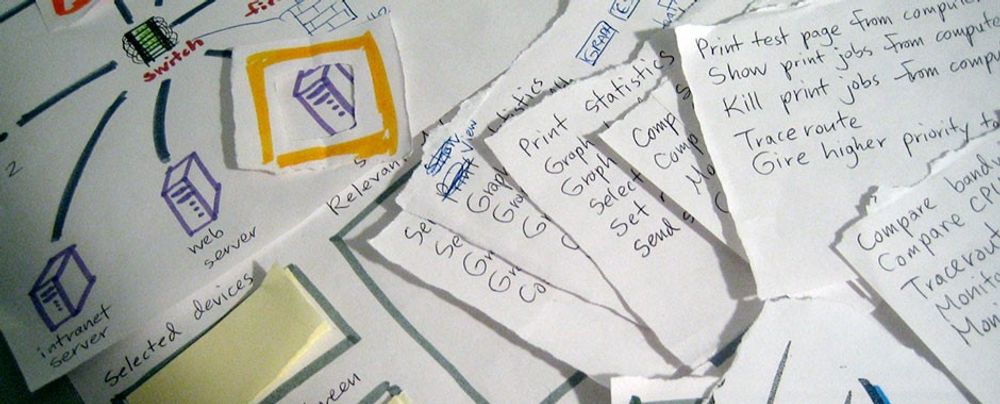

This chart shows a possible system of responses a wizard might use.

© NNG, Fair use

Decide what you want to learn: Are you testing how people phrase requests? Whether they trust a recommendation? How they react when the system makes a mistake?

Create a believable but simple interface. Digital design tools or even a printed paper interface can work—it depends on the fidelity you want.

Train the person acting as the wizard, so they understand the script, are ready to adapt, and remain invisible. If the system simulates typing, voice, or gesture recognition, the wizard should match the expected behavior convincingly.

Invite participants to complete tasks using the system. Observe closely—pay attention to confusion, hesitations, and off-script behavior—and let users speak freely and think aloud when possible.

After the session, ask participants for feedback. Then, adjust the prototype based on what you observed. If the concept is promising, you can gradually replace the wizard’s actions with real functionality.

Stay invisible: Keep the wizard out of sight for higher-fidelity prototyping; use one-way mirrors, partitions, or remote tools.

Be prepared; stay flexible: Create response scripts but allow for unscripted moments. Users are people—unexpected behavior often reveals the most useful insights.

Use short, focused sessions: Avoid long, tiring sessions—keep each test around 30–45 minutes.

Pilot first: Test the setup with teammates before involving participants.

Record sessions: With permission, capture screen and voice data. These help in later analysis.

Discover many helpful points about planning an observational study, as Alan Dix discusses:

1. Scalability and Repetition

Because it requires manual effort, Wizard of Oz testing doesn’t scale well—each session takes much human coordination and preparation.

2. Wizard Fatigue

The person acting as the wizard must stay focused and responsive; so, sessions that run too long or involve unpredictable user behavior can lead to errors.

3. Risk of Breaking the Illusion

If users realize a human is behind the scenes, it can bias results—they might behave unnaturally. Keep the setup believable and rehearse beforehand to minimize this.

4. Not a Replacement for Real Tech Testing

Eventually, you must validate whether the actual technology can perform as expected. WoZ prototyping and testing is a stepping stone—not a final proof.

5. It’s Not Suitable for Every Situation

It’s best to steer clear if: you’ve already got a working version of the system and want to test real performance; the concept doesn’t involve human-like intelligence or adaptive behavior; you need long-term, repeated use data; or you can’t ensure the illusion will hold (e.g., users are highly tech-savvy or suspicious).

WoZ sessions can surface precious insights—like unexpected things that users expected—for designers to refine requirements. The points where users felt delighted or the wizard struggled to simulate expected behavior can help prioritize features, define edge cases, and more—such as test speech patterns, misunderstandings, and repair strategies. Better still, session transcripts can serve as training data if teams want to build artificial intelligence (AI) or machine learning (ML) models.

With a unique blend of theatrical deception and strategic research, WoZ prototyping provides design teams with a much-needed safe zone in which to explore and trial ideas and features. When they do it well, they can power themselves along—if not the Yellow Brick Road of L. Frank Baum’s much-loved story—a path paved with golden blocks of essential insights about the people who will eventually use their intuitive products and enjoy fantastic digital experiences.

Take our course, Conducting Usability Testing for a treasure trove of vital insights and best practices about testing design solutions.

Enjoy our Master Class How to Get Started with Usability Testing with Cory Lebson: Principal User Experience researcher with 20+ years experience and author of The UX Careers Handbook.

Discover additional points and a helpful WoZ template in our article, 5 Common Low-Fidelity Prototypes and Their Best Practices.

Find a wealth of helpful insights and tips in the NNG article The Wizard of Oz Method in UX.

Explore more in UX 4Sight’s Wizard of Oz Prototyping: What It Is, How & Why It's Done.

Designers use Wizard of Oz prototyping to test digital products before they build any actual functionality. In this method, a human secretly performs functions that users think the system handles automatically. This lets designers explore ideas quickly, collect real user feedback, and refine the experience—all without heavy technical investment—and so they can prevent disappointments later in usability testing.

It works especially well in early design stages, where the team wants to validate core interactions or user flows without committing to coding. For instance, a voice assistant prototype might seem to understand spoken commands, but a person behind the scenes types responses manually. This creates the illusion of a finished product and reveals how users naturally interact with it.

Wizard of Oz testing has roots in behavioral psychology and simulates naturalistic conditions—a point that can make the finds all the more valid.

Explore the power of prototyping in this video, which addresses the Wizard of Oz approach to help guide towards better digital products:

Use a Wizard of Oz prototype when you need to test complex interactions, especially those involving AI, voice, or system intelligence—before investing in full development. This method works best in early design stages, where validating user behavior, expectations, and workflows matters more than building functionality.

For example, you can test how users interact with a chatbot, voice assistant, or recommendation engine by simulating system responses manually. You'll uncover usability issues, misunderstandings, and edge cases that might go unnoticed in static wireframes or mockups. This approach is even more attractive when time or budget constraints limit high-fidelity development.

Above all, Wizard of Oz prototyping helps reduce risk. With it, your team can catch interaction flaws early enough to slash corrective product costs. What's more, it also supports agile design as it enables rapid iteration and user-centered refinement.

Enjoy our Master Class Design For Agile: Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them with Laura Klein: Product Management Expert, Principal at Users Know, Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups.

Wizard of Oz prototyping works best for products that rely on complex or intelligent system behavior—especially ones that involve AI (artificial intelligence), natural language, automation, or personalization. Chatbots, voice assistants, recommendation engines, smart home interfaces, and other adaptive systems benefit the most because they're hard to prototype with traditional tools.

It's wise to use this method when the product's core value depends on how users interact with unseen “intelligence.” For example, a mental health app that simulates empathetic conversation, or a travel planner that offers smart itinerary suggestions, are things you can Wizard of Oz–test to observe how users respond before building real logic. The insights you get can help you design and refine more mindfully (especially important for something like a mental health app).

These prototypes help test assumptions early and reveal natural behaviors. This technique cuts development waste and improves usability outcomes in how it helps teams surface issues at the interaction level—before any code gets written.

For a wealth of insights into the exciting world of Designing with AI, enjoy our Master Class Conversation Design: Practical Tips for AI Design with Elaine Anzaldo, Conversation Designer, Meta.

To plan a Wizard of Oz prototype test, first define the core interaction you want to observe. Pick a task that involves system “intelligence” or dynamic responses—like booking through a chatbot or interacting with a voice assistant. Next, script realistic scenarios and user flows. Then assign someone to act as the “wizard” who mimics the system's behavior behind the scenes.

Set up the interface to look and feel functional—especially if it's a mid- to high-fidelity prototype, users should believe they're interacting with a real system directly. Avoid revealing the human involvement. Recruit target users and conduct usability testing while capturing feedback, confusion, and natural behaviors. Last, but not least, analyze the results carefully so you can refine your design before you move on to invest in development.

The WoZ method works because it keeps testing fast, low-cost, and focused. When you focus well on usability testing, you can come away with many nuggets of information you otherwise might have not revealed from your users.

To simulate system responses as the “wizard” in a WoZ session, start by preparing a detailed script or decision tree that covers likely user actions and expected system replies. Use real content and interface elements to keep the experience believable. During the test, monitor user input in real-time and respond quickly—ideally within one or two seconds—to keep up the illusion of automation.

You can simulate responses via chat interfaces, voice replies, or on-screen UI updates. Tools like shared screens, remote control software, or prototyping platforms (e.g., Figma or Axure) help you stay hidden while you are in control of what the user experiences.

Consistency matters. Stick to your script to avoid misleading users by ad-libbing with “irregular” details or introducing bias. Last, but not least, always debrief users afterwards to explain the setup—this protects ethical standards and builds trust, especially after something as “deceptive” as impersonating a machine.

To help keep a handle on reality—and the point that as humans we can only control a certain number and type of situations—get a deeper insight into the phenomenon called the illusion of control.

(Note: this is more for higher-fidelity WoZ prototypes.) To make sure participants don't know the system isn't real, design the prototype interface to look polished and fully functional. Don't include placeholders or obvious gaps that could give the “game” away. Set up a realistic context—like a branded app screen, a simulated chatbot, or voice interaction—with clear cues to guide users naturally.

Most importantly: keep the “wizard” hidden. Use a separate device, room, or remote setup so users don't see or hear anything unusual. Make sure the wizard responds promptly—ideally within 1–2 seconds—to maintain the illusion of automation. Plan for likely user actions in advance and rehearse different scenarios so you've got things covered on this front.

Don't overexplain the system beforehand; that might tip some users off to be on the look-out for something unusual. Just frame the test as a normal usability session. And then—after the test is over—always debrief participants to reveal the setup and respect their consent; it's good ethics.

The power of WoZ sessions lies in how users can suspend disbelief when the design feels smooth, responsive, and emotionally consistent. That's how WoZ prototypes mimic their namesake—the titular Wizard in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz—but just make sure nobody goes looking for your “wizard” or accidentally opens a door or curtain to find that person playing a convincing role; it'll spoil the effect, and findings.

Lift the lid on a whole treasure trove of usability testing advice in our Master Class How to Get Started with Usability Testing with Cory Lebson: Principal User Experience Researcher with 20+ years of experience and author of “The UX Careers Handbook.”

To keep bias away when acting as the wizard, follow a consistent script for every user. Predefine system responses based on expected inputs and stick to them. This reduces the chance that you might adjust replies subconsciously to guide or influence user behavior.

Stay neutral and “machine-like”—don't react verbally or nonverbally during the session. Avoid correcting users or giving hints. Let them explore the system as if it were real, even if they make mistakes. With users' consent (although only tell them it's a WoZ session afterwards), record sessions for later analysis instead of relying on memory, which can skew interpretation.

Conduct a pilot test to refine your script and timing, too. Consistency and preparation are key if you're going to keep the experience uniform across participants. When you control for bias in usability testing, it improves the accuracy of insights and leads to better design decisions.

To err might be human, but to minimize bias is “divine”—discover how bias can creep in and trip up research and design, and find tips on how to keep it at bay.

To pick tasks for a Wizard of Oz test, focus on high-impact, uncertain, or user-critical interactions—especially ones that involve system intelligence, automation, or personalization. To begin, identify the product's core value propositions. Then ask: What actions will users take to achieve these goals? Prioritize tasks that reveal user expectations or behaviors you can't predict.

Keep tasks realistic and goal-oriented. For example, in a voice assistant app, ask users to “find a vegan recipe” instead of testing abstract commands. Don't include overly scripted tasks that guide users too much—the goal is to observe natural interaction patterns.

It's a good idea to select 3–5 tasks, to keep the session focused and avoid fatigue. Most problems tend to surface after testing with just five users, so fewer but well-chosen tasks are highly effective.

For a deep-dive into the exciting world of discovering how users encounter your designs, take our course Conducting Usability Testing.

For all its powerful positives, Wizard of Oz prototyping does come with a few key risks. First, users might behave differently if they know or suspect a human controls the system. That can skew results and reduce test validity, and corrode trust—nobody likes to feel they have been “had,” even if the deception has a noble purpose. Second, the timing or tone of the wizard may unintentionally introduce inconsistencies or bias—especially if they stray from the script.

Another risk is how easy it is to overestimate how well a future system will work based on a perfectly executed simulation. After all, real systems may not match the smoothness of human responses. And because you are simulating behavior, you might miss technical constraints or scalability issues the real product will face. To proceed only on the basis of having one good WoZ session might be like training for a long swim in cold water by doing just a few laps in a heated pool: inadvisable.

Lastly, whoever plays the wizard might find it mentally demanding—and the role is prone to human error. Mistimed responses or emotional cues can break the illusion and disrupt the test; users might not show their suspicions outwardly, but their behavior can become unnatural very quicky once they believe something is going on behind the scenes.

Find helpful points and a WoZ template in our article, 5 Common Low-Fidelity Prototypes and Their Best Practices.

To analyze results from a Wizard of Oz prototype, review recordings and notes to identify patterns in user behavior, confusion points, unmet expectations, and emotional responses. Focus on how users interpret system feedback, how often they need help, and whether the interface guides them smoothly toward their goals.

Look for repeated friction points or breakdowns in trust—these signal usability issues or mismatched expectations. Compare user actions with your scripted flows: did users follow the expected path or take unexpected turns? Pay attention to where they hesitated or asked questions.

Organize findings by task and theme. Use tools like affinity mapping or journey mapping to visualize patterns. Then prioritize issues by severity and impact on user goals.

Wizard of Oz tests reveal how users interact with “intelligent” systems, even before coding begins, and give teams a great opportunity to refine the UX early.

Take an adventurous trip on the trail of users in our article Customer Journey Maps — Walking a Mile in Your Customer's Shoes.

Kelley, J. F. (1984). An iterative design methodology for user-friendly natural language office information applications. ACM Transactions on Office Information Systems, 2(1), 26–41.

Kelley's pioneering work introduces a human-centered, iterative design methodology specifically for developing natural language interfaces. The paper outlines the development of CAL (Calendar Access Language), an application enabling non-technical users to interact with calendar systems using plain English. Through six empirically grounded iterations involving real users, Kelley demonstrates how usability can be systematically improved by addressing user misunderstandings and expectations. The significance of this research lies in its early and influential emphasis on user testing and refinement—principles that are foundational to modern human-computer interaction and user experience design. The work remains a cornerstone in interface design methodology literature

Maulsby, D., Greenberg, S., & Mander, R. (1993). Prototyping an intelligent agent through Wizard of Oz. In Proceedings of the INTERACT '93 and CHI '93 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 277–284).

This study explores the use of WoZ prototyping in developing intelligent agents. By simulating agent behaviors, the researchers could study user interactions and expectations without fully developing the underlying AI. The findings underscore the method's effectiveness in identifying user needs and refining system behaviors, thereby influencing the design of intelligent systems and user-agent interactions.

Dow, S., MacIntyre, B., Lee, J., Oezbek, C., Bolter, J. D., & Gandy, M. (n.d.). Puppet prototyping: Wizard of Oz support throughout an iterative design process. Georgia Institute of Technology.

This paper explores the use of the Wizard of Oz (WOz) prototyping method in the iterative design of pervasive computing systems. The authors introduce "puppet prototyping," where a human operator (the "wizard") simulates system components to test user interactions before full system implementation. They discuss the integration of WOz techniques into the Designer's Augmented Reality Toolkit (DART), facilitating the creation and evolution of WOz interfaces. The paper highlights the benefits of using WOz throughout the design process, allowing designers to explore user interactions and system behaviors without the need for fully developed technologies. A case study involving a location-aware audio experience in a historic cemetery illustrates the practical application of these methods.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Wizard of Oz Prototypes by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Wizard of Oz Prototypes with our course Conducting Usability Testing .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your expert for this course:

Frank Spillers: Service Designer and Founder and CEO of Experience Dynamics.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!